In this tutorial, I will show you different ways to control multiple servo motors using Arduino. Specifically, we will work with one of the smallest servo motors available, the SG90 9g Micro Servo Motor. The basic principles and skills that you’ll learn in this tutorial apply to just about any type of servo motor you’ll work with in robotics.

Prerequisites

- You have the Arduino IDE (Integrated Development Environment) installed on either your PC (Windows, MacOS, or Linux).

You Will Need

This section is the complete list of components you will need for this tutorial.

- 1 Arduino Uno with USB Cable (sends the electrical pulses to the servo to tell it how much to rotate)

- 6 SG90 9g Micro Servo Motors

- 6 10k Ohm Potentiometers

- 4xAA Battery Holder with On Off Switch

- 4 AA Batteries

- 2 Solderless Breadboards (400 Point… you can put two boards together to make an 800 Point Breadboard)

- 1 Male-to-Female, Female-to-Female, and Male-to-Male Jumper Wires Kit

- Alligator Clip Kit

- 1 Toggle LED Switch

- 1 Momentary Push Button Switch

- 1 Arduino Sensor Shield V5.0

- 1 6-Channel Digital Servo Tester

- 1 DC Variable Power Supply

- 1 Breadboard Power Supply 5v/3.3v

- 4 9V Batteries

- 1 9V Battery Connector with Male DC Plug

Control a Single Servo Motor Using Arduino

The SG90 Micro Servo Motor has an operating voltage of 4.8V – 6.0V. Fortunately, the Arduino Uno board has a 5V pin. We can therefore, for the most basic setup, connect the motor directly to the Arduino.

In practice, you would want to use an external power supply for your servos rather than using the 5V pin of the Arduino. I’ll show you how to power an SG90 servo with an external power supply later in this tutorial. But, for now, I want to show you the most basic way to make a single servo motor move.

Here is the wiring diagram in pdf format.

- Connect the red wire (+V power wire) of the servo to the 5V pin of the Arduino Uno.

- Connect the brown wire (Ground wire) of the servo to the GND (ground) pin of the Arduino Uno. In the pdf diagram, the black wire = brown wire.

- Connect the orange control (Control Signal) wire of the servo to Digital Pin 9 of the Arduino Uno. This orange wire is the one that will receive commands from the Arduino. Pin 9 is one of Arduino’s Pulse-Width Modulation pins. In the pdf diagram, the yellow wire = orange wire.

Version 1

Power up your Arduino by plugging in the USB cord to your computer.

Open the Arduino IDE, and in a new sketch, write the following code. Save the file as sg90_using_arduino.ino:

/*

Program: Control the SG90 Micro Servo Motor Using Arduino

File: sg90_using_arduino.ino

Description: Causes the servo motor to sweep back and forth

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: June 20, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Create the servo object to control a servo.

// Up to 12 servo objects can be created on most boards.

Servo myservo;

void setup() {

// Attach the servo on pin 9 to the servo object

myservo.attach(9);

}

void loop() {

// Go from 0 degrees to 180 degrees

// Move in steps of 1 degree

for (int angle = 0; angle <= 180; angle += 1) {

// Tell servo to go to the position in variable 'angle'

// where 'angle' is in degrees

myservo.write(angle);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

// Go from 180 degrees to 0 degrees

// Move in steps of 1 degree

for (int angle = 180; angle >= 0; angle -= 1) {

// Tell servo to go to the position in variable 'angle'

// where 'angle' is in degrees

myservo.write(angle);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

}

Upload the code to your board. This code will make the shaft of the motor sweep back and forth 180 degrees.

If this is a new Arduino board that has never been connected to your computer before, you’ll need to go to Tools -> Port, and select the COM port your Arduino is connected to.

Version 2

Now write this code and upload it to your board. This code is more flexible because it allows you to have a template for when you might want to use more than one servo. Save the file as sg90_using_arduino_flex.ino:

/*

Program: Flexible Control of the SG90 Micro Servo Motor Using Arduino

File: sg90_using_arduino_flex.ino

Description: Causes the servo motor to sweep back and forth

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: June 20, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 1

// Create the servo object to control a servo.

Servo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servo to digital pin on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {9};

// Default angle for the servo in degrees

int default_pos[SERVOS] = {0};

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servo to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

// Make all the servos go to the default position

myservo[i].write(default_pos[i]);

}

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

void loop() {

// Go from 0 degrees to 180 degrees

// Move in steps of 1 degree

for (int angle = 0; angle <= 180; angle += 1) {

// Update the angle for all servos

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Tell servo to go to the position in variable 'angle'

// where 'angle' is in degrees

myservo[i].write(angle);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

}

// Go from 180 degrees to 0 degrees

// Move in steps of 1 degree

for (int angle = 180; angle >= 0; angle -= 1) {

// Update the angle for all servos

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Tell servo to go to the position in variable 'angle'

// where 'angle' is in degrees

myservo[i].write(angle);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

}

}

You should see the same behavior with this program as you did in the previous program you wrote.

Control a Servo Motor Using Arduino and a Potentiometer

In this section, we’ll use Arduino and a potentiometer to control the angle of the servo. By turning the knob on the potentiometer, we can control the voltage output of the potentiometer. This voltage output is read by the Arduino and is then mapped to some degree value between 0 and 180 degrees.

A potentiometer has 3 terminals:

- Two outer terminals are used for power: one outer pin connects to ground and the other connects to positive voltage. Potentiometers don’t have polarity, so it doesn’t matter which one is ground and which one is connected to positive voltage.

- A central control terminal is used for voltage output: turning the knob of the potentiometer increases or decreases the resistance, which lowers or increases the voltage output.

Here is the wiring diagram in pdf format.

Here is the code that you need to upload to your Arduino. Save it as sg90_using_potentiometer.ino:

/*

Program: Control the SG90 Using a Potentiometer

File: sg90_using_potentiometer.ino

Description: Turn the knob of the potentiometer to control the servo angle.

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: June 21, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 1

// Create the servo object to control a servo.

Servo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servo to digital pin on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3};

// Analog pin used to connect the potentiometer

int potpin = A0;

// Variable to read the value from the analog pin

int pot_pin_val;

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servo to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

}

}

void loop() {

// Reads the value of the potentiometer (value between 0 and 1023)

pot_pin_val = analogRead(potpin);

// Scale it to use it with the servo (value between 0 and 180)

pot_pin_val = map(pot_pin_val, 0, 1023, 0, 180);

// Update the angle for all servos

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

myservo[i].write(pot_pin_val);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

}

Turn the knob to control the servo.

This code above can work with other servos that can operate with 6V. Below you see the same code run when I connected the popular MG996R servo.

Control 6 Servo Motors Using Arduino

In this section, we’ll control 6 SG90s using Arduino. The use case for using 6 servo motors is a robotic arm. Robotic arms traditionally have 6 degrees of freedom (one motor for each degree of freedom). What does degrees of freedom mean? Here is the definition:

Degrees of freedom is the number of independent variables that are needed to fully specify the configuration of a robot.

For example, imagine you are trying to specify the position and orientation of a gripper on the end of a robotic arm. This robotic arm exists in a three-dimensional space, which means that you can fully specify its configuration with just 6 variables (degrees of freedom):

- Three translational degrees of freedom: x, y, and z, which describe the linear motion of the robot back and forth along those axes

- Three rotational degrees of freedom: roll, pitch, and yaw, which describe the rotational motion about the x, y, and z axes, respectively.

The cover image on this page shows the 6 different degrees of freedom of a rigid body (like a robotic arm) in a three-dimensional space.

A servo motor is restricted to sweeping back and forth along a single plane, so its configuration can be fully specified by only one variable (it’s angle, which on many servos goes from 0 to 180 degrees). Therefore, if you want to have a robotic arm that can move to any position in a three-dimensional space, you need to have at least six motors.

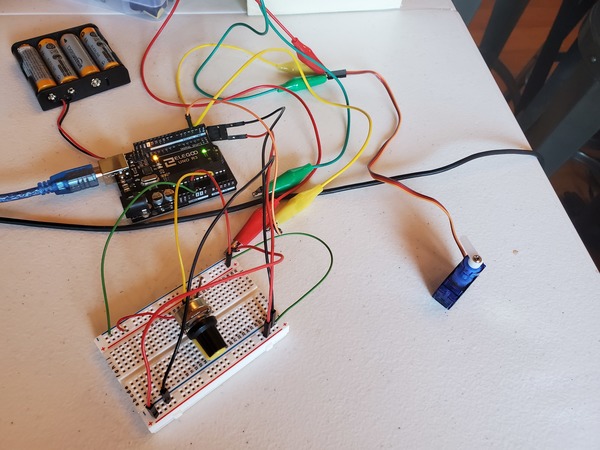

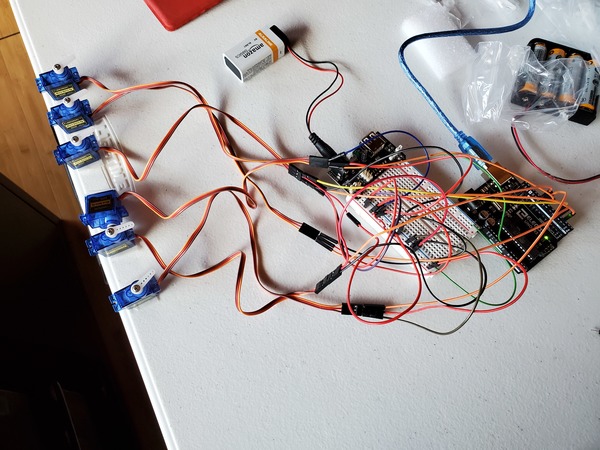

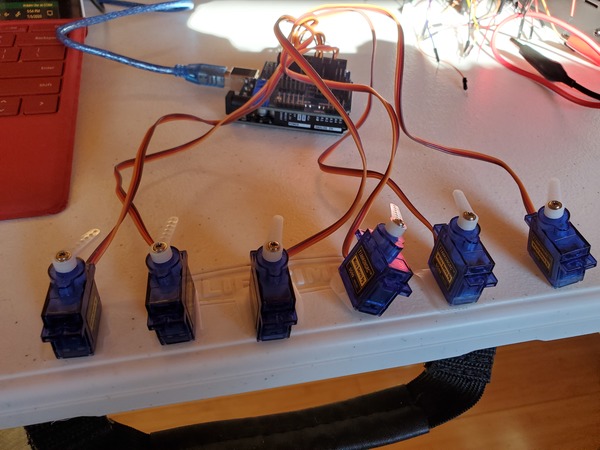

With that background, let’s take a look at how to control 6 SG90 servos using Arduino. Let’s add five servo motors to your setup as well as an external power supply (4 x AA batteries).

Once you’ve wired it up, upload the sg90_using_arduino_flex.ino (or the sg90_using_arduino.ino file, both work the same way) file you used earlier. You don’t need to make any modifications to the code since all servos receive the same control signal from digital pin 9 of the Arduino.

You should see the six servo motors rock back and forth.

Control 6 Servo Motors Independently Using Arduino

In this section, we will cause the servos to rotate independently. Each servo will be attached to its own control pin on the Arduino.

Each servo will run through a loop of increments of 30 degrees for their full range of rotation (i.e. 0 to 180 degrees).

Each servo will move back and forth, repeating this process over and over again.

Note that you need to connect the ground of the battery pack to the ground of your Arduino board. Doing this ensures that they have the same 0V reference point (i.e. Ground with respect to the Arduino’s power supply is the same Ground with respect to the motor’s power supply).

Here is the code. Save it as control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino.ino:

/*

Program: Control 6 SG90s Independently Using Arduino

File: control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino.ino

Description: Control 6 servos independently using Arduino.

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: June 29, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 6

// Define the number of states

#define STATES 7

// Create the servo objects.

Servo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servos to digital pins on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3,5,6,9,10,11};

// Potential angle values of the servos in degrees

int angle_states[STATES] = {180, 150, 120, 90, 60, 30, 0};

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servo to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

// Wait 500 milliseconds

delay(500);

}

}

void loop() {

// Move in one direction.

for(int i = 0; i < STATES; i++) {

myservo[0].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[1].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[2].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[3].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[4].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[5].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

}

// Move in the other direction

for(int i = (STATES - 1); i >= 0; i--) {

myservo[0].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[1].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[2].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[3].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[4].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

myservo[5].write(angle_states[i]);

delay(100);

}

}

Upload the code to your Arduino board, and watch the servos run through the different angles.

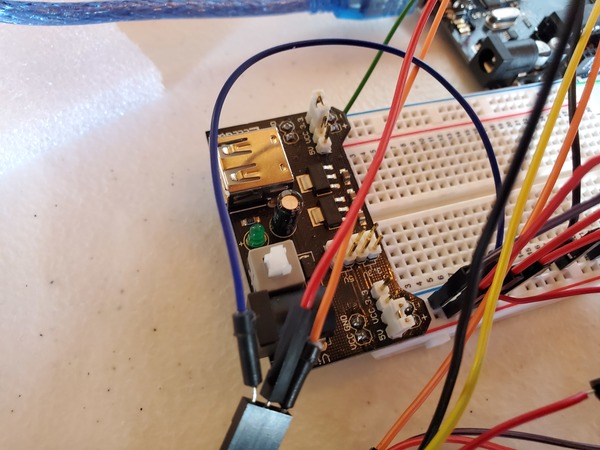

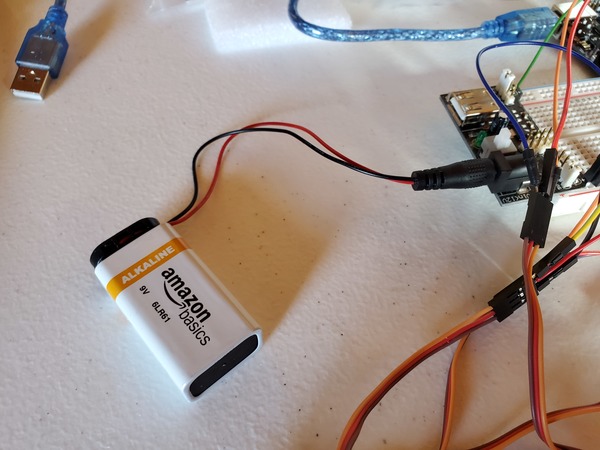

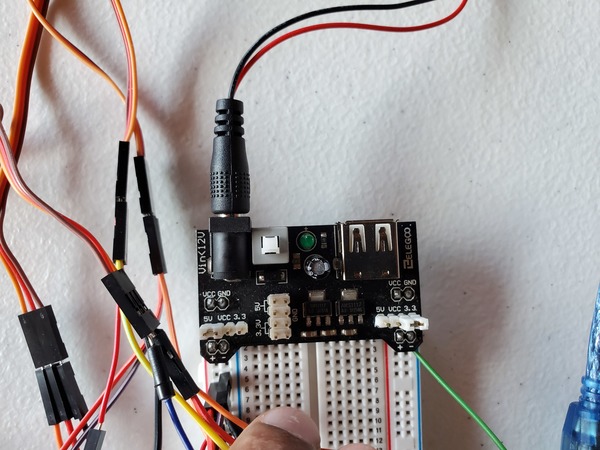

Control Servo Motors Using a Breadboard Power Supply

In this section, we will power the breadboard with the breadboard power supply instead of the 4 x AA battery pack.

Grab a 9V battery and a 9V battery connector. Also grab the Breadboard Power Supply 5v/3.3v.

Attach the battery connector to the 9V battery.

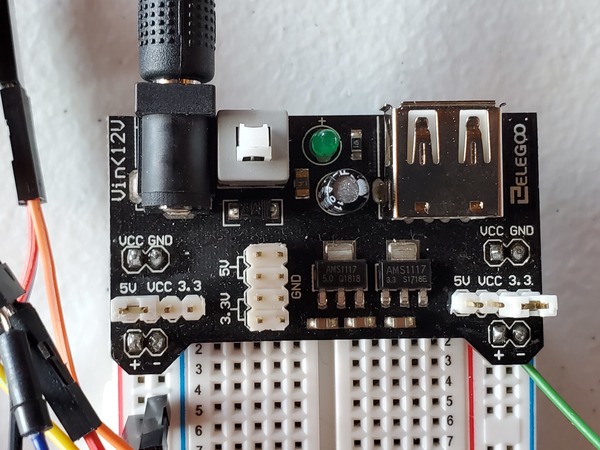

Place the breadboard power supply on the breadboard. The 5V pin (+) of the breadboard power supply needs to sink into the red (positive) rail of the breadboard. The ground (-) pin needs to sink into the blue (negative rail) of the breadboard.

On the other side of the breadboard, you can ignore the 3V pin (+) of the breadboard power supply. You don’t need it. Make sure that no wires are electrically connected to that pin. There is a negative (-) pin next to that VCC 3.3 + in. That one connects to the blue (GND) rail of the breadboard. That blue ground rail of the breadboard connects to the Arduino.

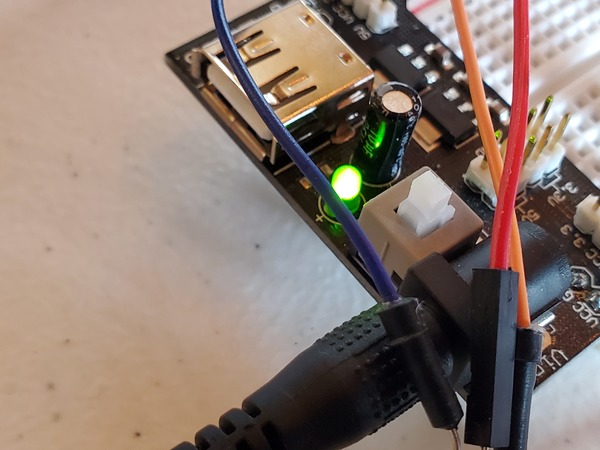

Now switch on the breadboard power supply. The switch is located next to the Vin>12V power supply connection of the breadboard. To switch it to ON, just push that button. A light (LED) will illuminate.

Launch the Arduino IDE, and load the following program (control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v2.ino) to the board. You should see the motors sweep back and forth in unison.

/*

Program: Control 6 SG90s Independently Using Arduino

File: control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v2.ino

Description: Control 6 servos independently using Arduino.

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: July 2, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 6

// Define the delay in milliseconds between sending instructions to individual servos

// I found this value through trial and error.

#define SERVO_DELAY 30

// Define the number of states

#define STATES 7

// Create the servo objects.

Servo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servos to digital pins on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3,5,6,9,10,11};

// Potential angle values of the servos in degrees

int angle_states[STATES] = {180, 150, 120, 90, 60, 30, 0};

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servo to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

// Wait 500 milliseconds

delay(500);

}

}

void loop() {

// Move in one direction.

for(int i = 0; i < STATES; i++) {

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle

rotate_servos(

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i]);

}

// Move in the other direction

for(int i = (STATES - 1); i >= 0; i--) {

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle

rotate_servos(

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i]);

}

}

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle in degrees

void rotate_servos(

int joint_angle_0,

int joint_angle_1,

int joint_angle_2,

int joint_angle_3,

int joint_angle_4,

int joint_angle_5

){

myservo[0].write(joint_angle_0);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

myservo[1].write(joint_angle_1);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

myservo[2].write(joint_angle_2);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

myservo[3].write(joint_angle_3);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

myservo[4].write(joint_angle_4);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

myservo[5].write(joint_angle_5);

delay(SERVO_DELAY);

}

When you’re done, you can upload a blank sketch to your Arduino, or you can press the push button switch on the breadboard power supply.

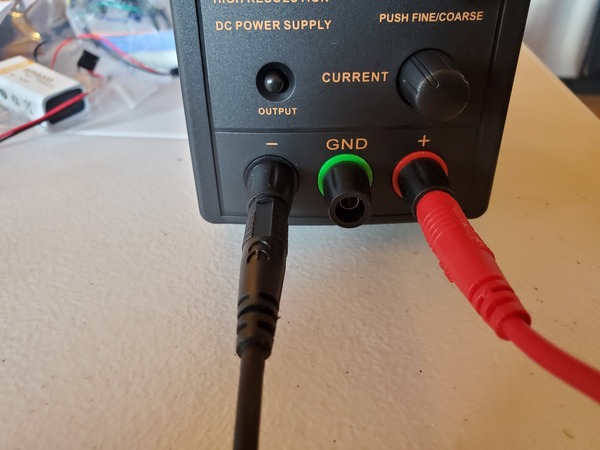

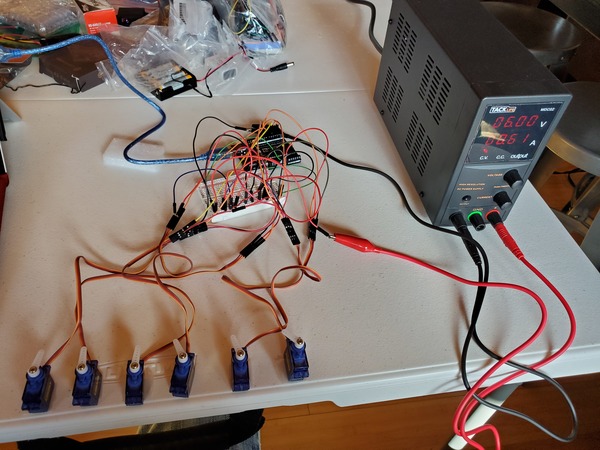

Control Servo Motors Using a DC Variable Power Supply (“Bench Power Supply”)

Now that we’ve seen how the breadboard power supply works, let’s see how we can connect a DC variable power supply.

I just bought this new power supply off Amazon. At the time of this writing, it was about $100.

To get it setup, you first need to push the black alligator clip lead into the negative (-) hole of the power supply.

Then push the red alligator clip lead into the positive (+) hole of the power supply.

Grab the power cord and plug it into the back of the power supply.

Plug the power cord into the wall socket, and turn the switch on the back of the power supply to ON.

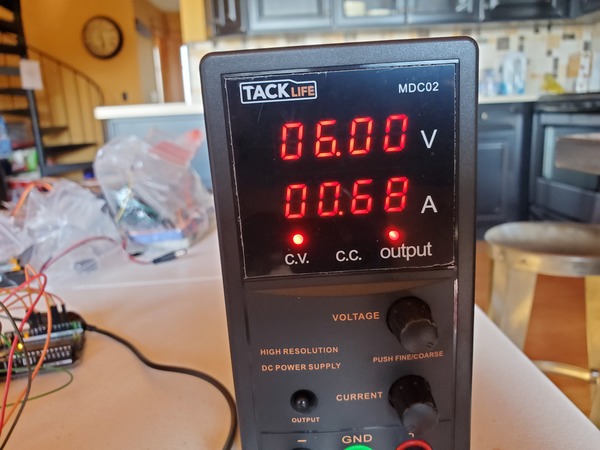

The operating voltage range for the SG90 servos is from 4.8V to 6V, so we will turn the VOLTAGE knob on the power supply to 6.00V. The power supply will provide a constant voltage at that level as long as the current drawn by the motor is less than the current limit.

If the current drawn exceeds the current limit, the voltage will drop, and the power supply will switch to constant current mode (CC light will come on).

Now we need to set the current limit. The current draw for each servo when moving is 100-250mA during movement.

We have 6 servos that each draw current. I will start at 600mA (6 x 100mA) for the limit and gradually turn the CURRENT knob to 800mA. Note that 600mA is 0.60 amps.

Push the CURRENT knob on the power supply to toggle the precision of the knob adjustments.

If you want to lock the voltage and current settings, you can push the current and voltage knobs at the same time for three seconds. To unlock these settings, you can push the current and voltage knobs for three seconds again.

Add a male-to-male jumper wire to both the black and red alligator clips.

Stick the jumper wires into the blue (-) and red (+) rails of the breadboard, just as you did earlier with the 4xAA battery pack.

Plug in your Arduino, and open the IDE.

Load control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v2.ino to your Arduino board.

On the power supply, press the output button to turn on the voltage. Your motors should sweep back and forth.

If the CC (constant current) light keeps blinking, turn the CURRENT knob (yes, while the motors are still moving) to increase the current. You want to increase the current limit to a level that keeps the power supply in CV (constant voltage) mode.

I can see that the motors are drawing about 710mA at peak current. Setting the current limit to 0.80A (800mA) worked perfectly for me.

At 0.60A, I found that the power supply kept switching to CC mode from CV mode…which means the current limit on the power supply is too low.

When you want to turn the voltage off, press the output button again.

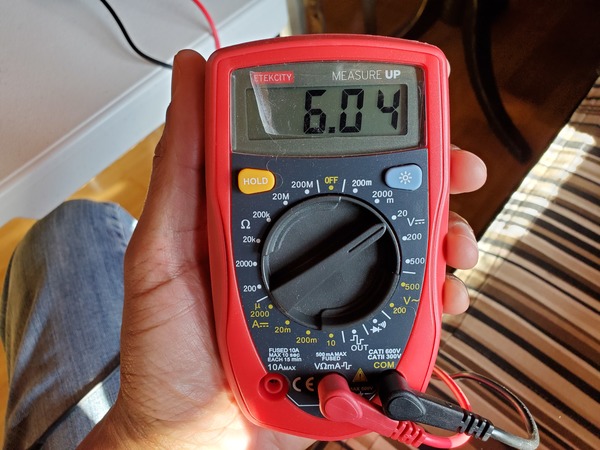

When you hook up the power supply to leads on a multimeter (if you have one), you should see that the voltage might be slightly above 6V. That’s fine.

Control a Servo Motor Using a Toggle LED Switch

Let’s use a toggle LED switch so that we can have another way to control when the motors are on and off.

Our electrical setup will remain much the same. However, we need to make the following changes.

- Connect the black alligator clip (-) of the power supply to the middle pin of the toggle LED switch.

- Using an alligator clip, connect the the third pin of the toggle LED switch (the “load pin”…the one on the end that is NOT gold in color) to the black jumper wire that connects to the blue power rail (-) of the solderless breadboard (the rail that is connected to the Ground wire of the six motors).

- The red alligator clip (+) of the power supply still needs to connect directly to the red (+) rail of the solderless breadboard via a jumper wire.

We will just use two pins of the switch. You don’t need to connect anything to the gold pin (i.e. Ground pin) of the switch.

Load control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v2.ino to your Arduino board.

Make sure the voltage is 6V, and the current limit is 0.60A.

Turn on the power supply.

Turn the switch to ON.

You should see the motors rocking back and forth.

Control a Servo Motor Using a Momentary Push Button Switch

The momentary push button switch is roughly the exact same setup as in the previous section. However, since you only have two pins on the button, you only need to connect those pins.

- You connect the black alligator clip (-) of the power supply to one of the pins of the switch (It doesn’t matter which one).

- The other pin of the switch connects electrically to the blue (-) rail of the solderless breadboard.

You can run the same Arduino program as before. When you turn on the power supply and push the switch, the motors will rock back and forth. When the switch is not pressed, electricity will not flow, and the motors will not move.

Control the Speed of Servo Motors

Up until now, the only thing we have been concerned about is how to move the angle of a servo. We have the code we wrote in Arduino tell the motor what angle we want, and the servo moves to that angle.

But how do we control the speed of a servo? If we have a walking, humanoid bipedal robot, for example, we might not want the servo to always move at full speed to our desired angle.

Fortunately, there is a library that can enable us to move the servo to our desired angle at a desired speed. The name of this Arduino library is called VarSpeedServo.

Go over to the GitHub page for the VarSpeedServo library, and download the zip file by clicking on the big green button on that page.

After you click the green button, there is an option to, “Download ZIP.” Click it.

Now, open the Arduino IDE.

Go to Sketch -> Include Library -> Add ZIP Library. Find the library in your system, and click Open.

The library is now in your system.

Now, let’s modify the control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v2.ino code. We will call the file control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v3.ino.

Open a new sketch, and type the following code. You see that we have an extra parameter in the code to control the speed of the motion of the servo (in addition to the angle):

/*

Program: Control 6 SG90s Independently Using Arduino

File: control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v3.ino

Description: Control 6 servos independently using Arduino.

Code Reference: https://github.com/netlabtoolkit/VarSpeedServo

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: July 3, 2020

*/

#include <VarSpeedServo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 6

// Define the number of states

#define STATES 7

// Create the servo objects.

VarSpeedServo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servos to digital pins on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3,5,6,9,10,11};

// Potential angle values of the servos in degrees

// Angles are measured from the positive x-direction (imagine a standard x-y graph)

// Therefore, 180 degrees is left, 0 degrees is right.

int angle_states[STATES] = {180, 150, 120, 90, 60, 30, 0};

// Speed of the servo motors

// Speed=1: Slowest

// Speed=255: Fastest.

const int go_slow = 50;

const int go_fast = 250;

// Set the default desired speed

int desired_speed = go_slow;

// Toggle to make servo go fast or slow

bool speed_flag = false;

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servo to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

}

}

void loop() {

// We will alternate the servo speed,

// going fast and then going slow

if (speed_flag == false) {

desired_speed = go_slow;

}

else {

desired_speed = go_fast;

}

// Move in one direction.

for(int i = 0; i < STATES; i++) {

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle

// at the desired speed

rotate_servos(

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

desired_speed);

}

// Move in the other direction

for(int i = (STATES - 1); i >= 0; i--) {

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle

// at the desired speed

rotate_servos(

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

angle_states[i],

desired_speed);

}

// Toggle the speed flag. If fast, go slow the next iteration.

// If slow, go fast the next iteration.

speed_flag = !speed_flag;

}

// Rotate the servos to the desired angle (in degrees) at the desired speed

void rotate_servos(

int joint_angle_0,

int joint_angle_1,

int joint_angle_2,

int joint_angle_3,

int joint_angle_4,

int joint_angle_5,

int speed_of_servo

){

// Angle range is 0 to 180 degrees, which corresponds to a pulse width

// of 500 to 2400 microseconds

// If the third parameter is true, we will wait for the servo

// to complete its movement before we jump to the next

// instruction.

myservo[0].write(joint_angle_0, speed_of_servo, true);

myservo[1].write(joint_angle_1, speed_of_servo, true);

myservo[2].write(joint_angle_2, speed_of_servo, true);

myservo[3].write(joint_angle_3, speed_of_servo, true);

myservo[4].write(joint_angle_4, speed_of_servo, true);

myservo[5].write(joint_angle_5, speed_of_servo, true);

}

You will see the motors sweeping back and forth, alternating between fast and slow.

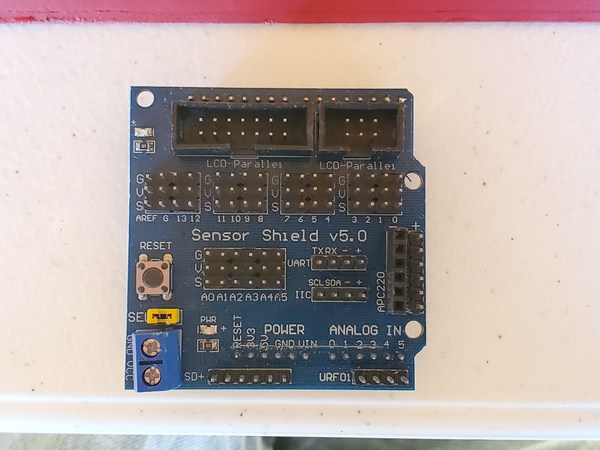

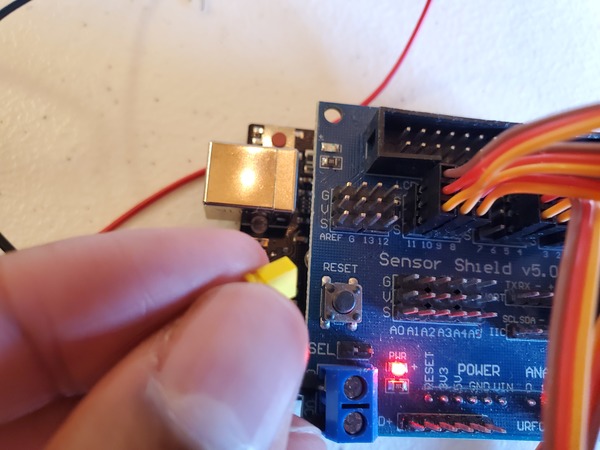

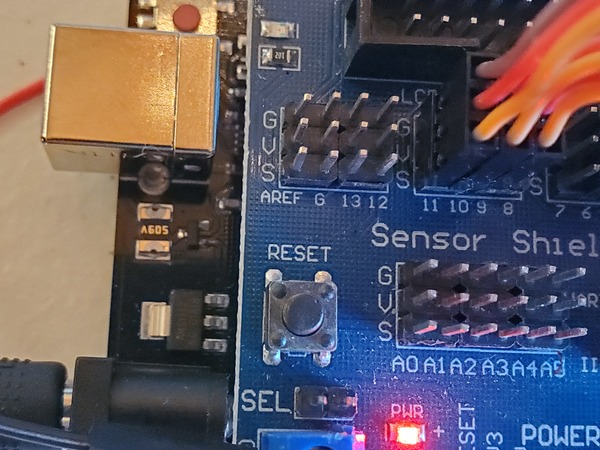

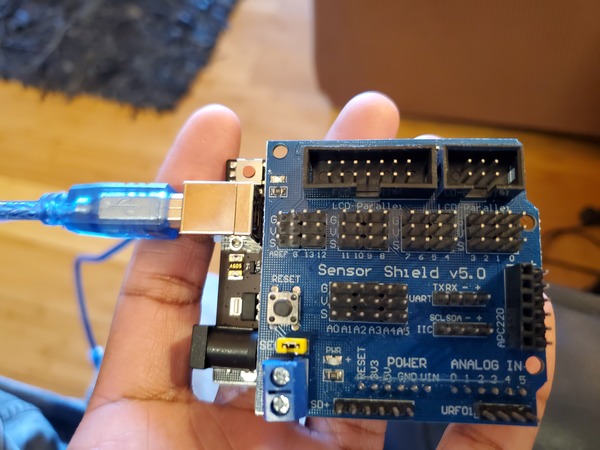

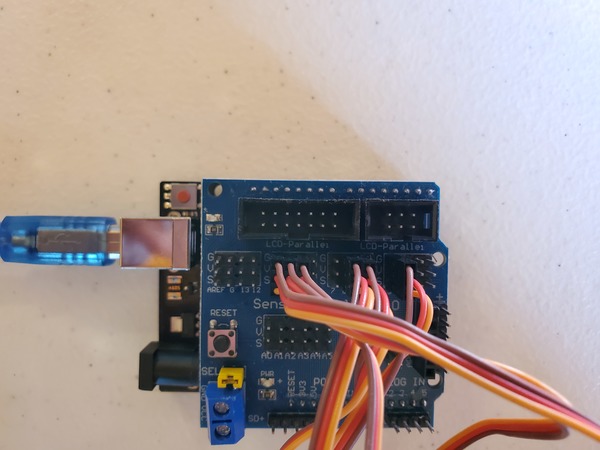

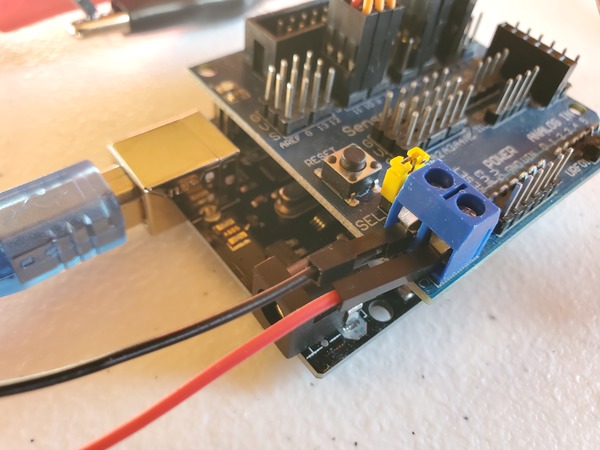

Control Servo Motors Using an Arduino-Compatible Sensor Shield

Now let’s use the Arduino Sensor Shield V5.0 to control the servos. The good thing about the sensor shield is that we don’t have to use the solderless breadboard anymore.

We can plug the external DC power supply (or 4xAA battery pack) directly into the power pins of the sensor shield.

This tutorial here shows how you can control the amount of power that goes to different parts of the sensor shield. We will just use an external power supply of 6V, which means that both the Arduino and the shield will be powered off the 6V.

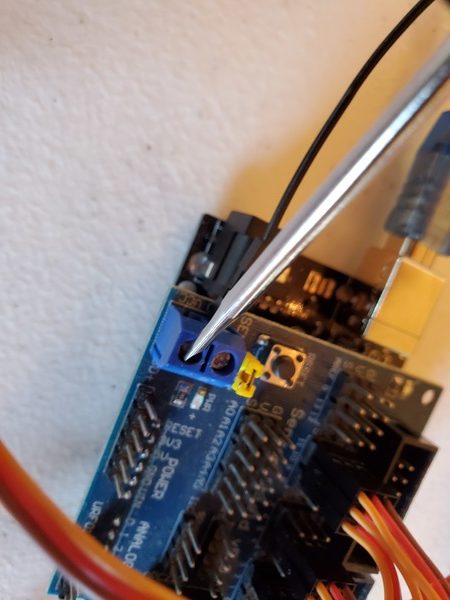

If you remove the yellow cover on the power selector (labeled SEL), the Arduino will be powered on its own power supply (assuming you plug in a 9V battery in the Arduino), while the sensor shield will be powered off the external DC variable power supply. You don’t need to remove it. I’m just demonstrating below what removing the yellow cover would look like.

OK, let’s get everything setup.

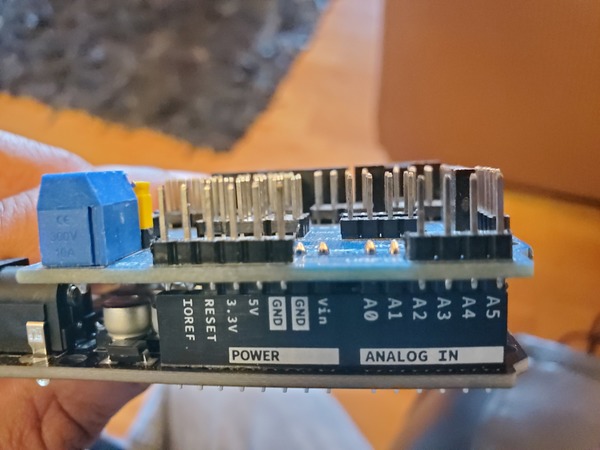

Grab the sensor shield and sink it on top of the Arduino. The bottom front pins of the sensor shield need to sink into the front pins of the Arduino.

Here is the pdf of the wiring diagram. Wire it up like you see in the diagram. Go slowly so that you get all the connections right.

Connect the DC variable power supply to the blue piece (or connect a 4xAA battery pack). Set it at 6V with 0.80A current limit. The black clip goes to the negative (-) terminal, and the red clip goes to the positive (+) terminal. You will need to unscrew the screw at the top, slip the wire in the bottom, and then tighten the screw.

The USB cable that is plugged into the Arduino isn’t plugged into anything.

Load the control_6_sg90s_independently_using_arduino_v3.ino program to your Arduino. Now, unplug the USB cable from your computer so that the Arduino is not connected to your computer.

If you’re using the DC variable power supply, you can press the “OUTPUT” button to give your sensor shield electricity.

You should see the servos sweeping back and forth, alternating between fast motion and slow motion.

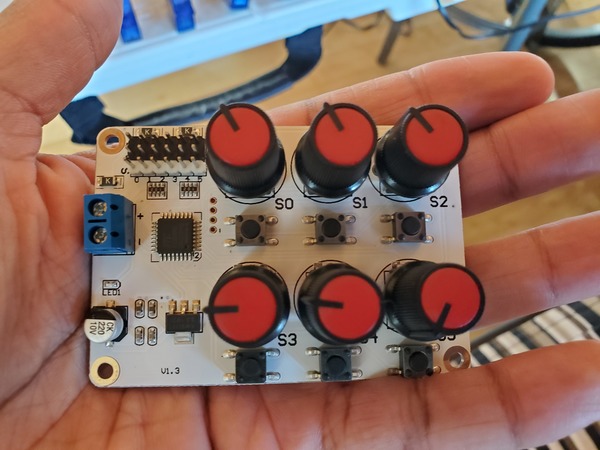

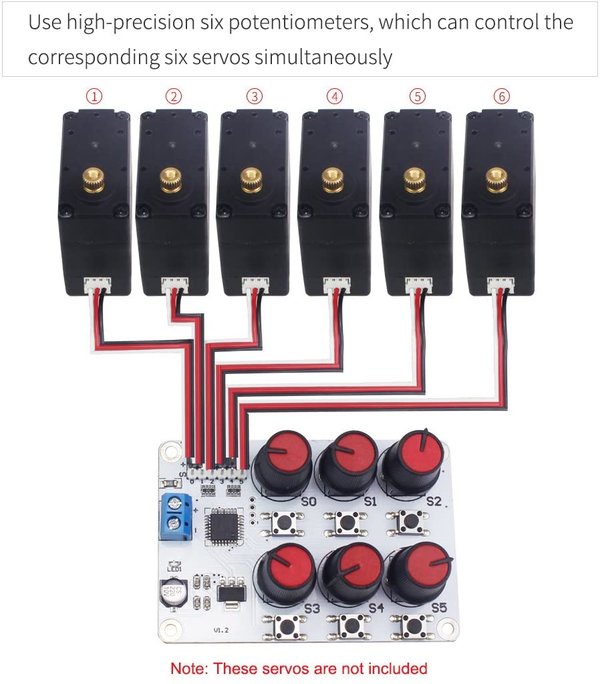

Control Servo Motors Using a 6-Channel Digital Servo Tester

Let’s use a 6-channel digital servo tester to control the servo motors. The digital servo tester comes equipped with 6 potentiometers that enable you to control each servo. It has a voltage range of 5 to 8.4V. It is a good tool to use when you purchase new servos and want to test to see if they work.

To set it up, plug each motor into the pins as shown below. The brown wire goes to (-), the red wire goes to (+), and the orange wire goes to signal (S).

There is a small button under each knob of. When you press it, the servo motor will lock to its center state. When locked, you won’t be able to control the servo.

To unlock the servo, you need to press the button again.

The servo tester works with a power supply of 5-8.4V according to the page on Amazon where I purchased this tester. Since our motors can work with 6V, I’ll stick with 6V as the voltage and put a current limit of 0.80A (800 mA). If you’re using a 4xAA battery pack, you don’t need to worry about this.

The blue piece on the digital servo tester is where you connect the power. You connect it just like you connected the blue piece in the previous section. Connect the red alligator clip (via a jumper wire) of the power supply (either 4xAA battery pack or the DC power supply like I’m using) to the + terminal. Connect the black alligator clip (via a jumper wire) of the power supply to the – terminal.

That’s all you need. You don’t need an Arduino at all. Turn the power ON on the power supply, and you can make each motor move by turning any of the 6 potentiometer knobs on the servo tester.

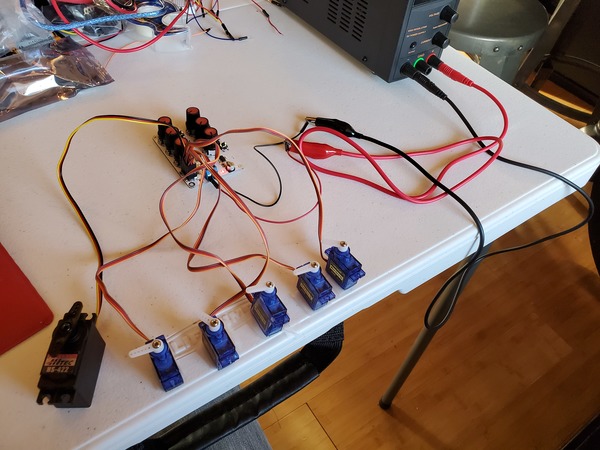

You can see in the image below, that you can use the tester to test many kinds of servos, including HS-422s and MG-996R servos that are commonly found in robotics projects.

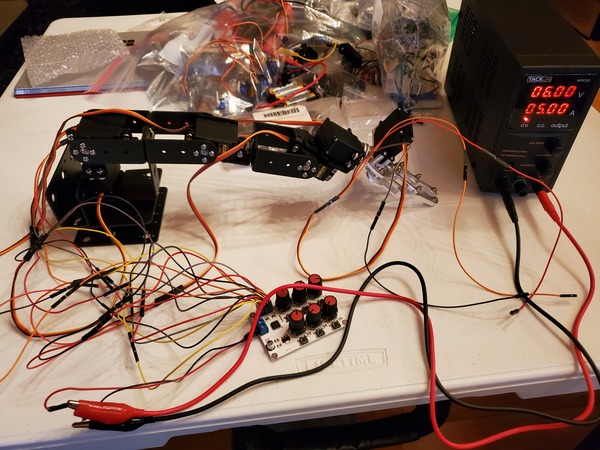

In this image, I’m using the servo tester to control a robotic arm. I’m using 6 servos (all MG-996R). The voltage on the power supply is 6V, and I set a maximum current of 5.00A.

According to the MG-996R datasheet, the running current at 6V is 500mA to 900mA (0.50A to 0.9A). The stall current is 2.5A. The stall current is the maximum current drawn when the motor is applying maximum torque (i.e. rotational force).

Therefore, I could have set a current limit of 1.00A per motor and been just fine.

Control 6 Servo Motors Using Potentiometers

One more thing. Let’s say that you want to control six different servo motors using the Arduino Sensor Shield v5.0 and potentiometers.

Here is the wiring diagram to do that.

Here is the code using the Servo library.

/*

Program: Control 6 Servos Using Arduino, Sensor Shield v5.0, and Potentiometers

File: control_6_servos_with_potentiometer_servo_lib.ino

Description: Turn the knob of the potentiometers

to control the angle of the 6 servos.

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: July 9, 2020

*/

#include <Servo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 6

// Create the servo objects.

Servo myservo[SERVOS];

// Attach servos to digital pins on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3,5,6,9,10,11};

// Analog pins used to connect the potentiometers

int potpins[SERVOS] = {A0,A1,A2,A3,A4,A5};

// Variables to read the value from the analog pin

int potpin_val[SERVOS];

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servos to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

}

}

void loop() {

// For each servo

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Read the value of the potentiometer (value between 0 and 1023)

potpin_val[i] = analogRead(potpins[i]);

// Scale value to between 0 and 180

potpin_val[i] = map(potpin_val[i], 0, 1023, 0, 180);

// Update servo position

myservo[i].write(potpin_val[i]);

// Wait 15 milliseconds for the servo to get to the position

delay(15);

}

}

Here is the code using the VarSpeedServo library.

/*

Program: Control 6 Servos Using Arduino, Sensor Shield v5.0, and Potentiometers

File: control_6_servos_with_potentiometer_varspeedservolib.ino

Description: Turn the knob of the potentiometers

to control the angle of the 6 servos.

This program enables you to control the speed of the servos

as well.

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Website: https://automaticaddison.com

Date: July 9, 2020

*/

#include <VarSpeedServo.h>

// Define the number of servos

#define SERVOS 6

// Create the servo objects.

VarSpeedServo myservo[SERVOS];

// Speed of the servo motors

// Speed=1: Slowest

// Speed=255: Fastest.

const int desired_speed = 50;

// Attach servos to digital pins on the Arduino

int servo_pins[SERVOS] = {3,5,6,9,10,11};

// Analog pins used to connect the potentiometers

int potpins[SERVOS] = {A0,A1,A2,A3,A4,A5};

// Variables to read the value from the analog pin

int potpin_val[SERVOS];

void setup() {

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Attach the servos to the servo object

myservo[i].attach(servo_pins[i]);

}

}

void loop() {

// For each servo

for(int i = 0; i < SERVOS; i++) {

// Read the value of the potentiometer (value between 0 and 1023)

potpin_val[i] = analogRead(potpins[i]);

// Scale value to between 0 and 180

potpin_val[i] = map(potpin_val[i], 0, 1023, 0, 180);

// Update servo position

// Angle range is 0 to 180 degrees, which corresponds to a pulse width

// of 500 to 2400 microseconds

// If the third parameter is true, we will wait for the servo

// to complete its movement before we jump to the next

// instruction.

myservo[i].write(potpin_val[i], desired_speed, true);

}

}

Troubleshooting Servo Motors That Jitter or Move Erratically

If you have servo motors that seem to have a mind of their own, try the following steps below.

Double-Check Your Wiring

Make sure that your wiring is correct. Also, make sure that the ground of the Arduino is connected to the ground of your motors so that they have the same 0V reference point.

Double-Check Your Code

Go through your code line by line to make sure the logic is correct.

Use a Stronger Microcontroller

The Arduino Uno is good for some things, but it can present some problems when you are trying to drive a lot of motors (e.g. with a robotic arm). It is limited in memory space.

Try the Arduino Mega 2560 Rev 3 instead. It has more memory and can better handle a large amount of processing. And don’t use a sensor shield (i.e. get rid of the “middle man”).

Get Better Quality Servo Motors

Servo motors like the MG-996R and the SG90 aren’t that powerful. They have trouble lifting even the smallest of loads. Try using a 20 kg digital servo (or higher) if you run into issues with the motor not being able to lift something.

While the servos we used in this tutorial were just a few dollars each, there are also servos out there (often called “smart servos”) that can cost hundreds of dollars.

For example, the Dynamixel (Dynamic + Cell) servos are some of the best servos on the market. Sure they’re expensive, but they are loaded with a bunch of bells and whistles, including position feedback (i.e. bi-directional communication so you can get a reading on where your servos are at any given time).

Get a Good Quality Power Supply

Batteries are OK, but if you have to test a lot of motors, I highly recommend buying a DC bench power supply. Specifically, look to get a DC Adjustable Power Supply Capable of 30V/10A.

It will save you a lot of money down the road, and prevent you from draining through tons of batteries.

Patience and Persistence

If none of the troubleshooting tips above work for you, don’t give up! Robotics can be downright frustrating sometimes when something doesn’t work like it should. If all else fails, start from scratch, and put together each piece of hardware and software one step at a time.

That’s it for now. Keep building!