When you build a mobile robot, one of the most important things to consider is how the robot will figure out where it is and which direction it’s facing. This process is called localization.

Imagine you’re blindfolded and placed in a room. You might be able to feel around and make guesses about where you are based on what you touch, but it would be much easier if you could see.

This is where the ROS2 robot_localization package comes in. It’s like giving your robot a special superpower to combine (or “fuse”) information from different sensors, like wheel encoders and an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), to better understand its position and orientation.

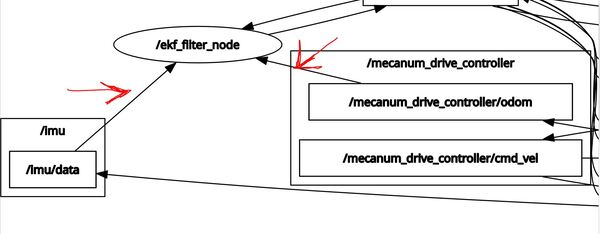

In this tutorial, I will show you how to set up the robot_localization ROS 2 package on a simulated mobile robot. We will fuse odometry data from the /mecanum_drive_controller/odom topic (which is like the robot counting its own steps) with IMU data from the /imu/data topic (which tells the robot if it’s tilting or turning). By combining these two sources of information using a special mathematical tool called an Extended Kalman Filter, our robot will have a much better idea of where it is and which way it’s pointing.

Why is this important? Here are a few reasons:

- Correcting Wheel Slip: Sometimes the robot’s wheels can slip, causing inaccurate data. By fusing data from both the wheels and the IMU, we can correct these errors and improve the robot’s navigation.

- Enhancing Navigation: Accurate data from sensor fusion allows the robot to navigate more efficiently, making fewer mistakes and taking more precise paths.

- Improving Reliability: Combining multiple data sources makes the robot’s movement data more reliable, even if one of the sensors temporarily fails or provides bad or noisy data.

- Optimizing Performance: With smoother and more accurate movement data, the robot can perform tasks more effectively, whether it’s moving objects, exploring new environments, or performing complex maneuvers.

Let’s get started!

If you prefer learning by video, watch the video below, which covers this entire tutorial from start to finish.

Prerequisites

- You have completed this tutorial: How to Install ROS 2 Navigation (Nav2) – ROS 2 Jazzy.

- You have completed this tutorial: Understanding Coordinate Transformations for Navigation.

All my code for this project is located here on GitHub.

What is an Extended Kalman Filter?

The engine behind the robot_localization package for ROS 2 is an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). The default name of the ROS 2 node is ekf_node.

An EKF is a mathematical algorithm that combines data from different sensors to figure out a robot’s position, which way it’s facing, and how fast it’s moving. It does this by constantly making educated guesses based on how the robot is expected to move, and then fine-tuning these guesses using the actual sensor readings. This helps to smooth out any noise or inaccuracies in the sensor data, giving us a cleaner and more reliable estimate of where the robot is and what it’s doing.

One of the best things about the EKF is that it can handle noisy sensor data. It’s smart enough to trust the sensors that are more likely to be accurate, while still using data from the less precise sensors. This means that even if one sensor is a bit inaccurate, the EKF can still do a good job of locating the robot by relying more on the other sensors.

Another great aspect of the EKF is that it can keep working even if a sensor stops providing data for a little while. It does this by using its educated guesses and the last known sensor readings to keep tracking the robot. When the sensor starts working again, the EKF smoothly brings the new data back into the mix. This helps to keep the robot’s location estimates reliable, even if things get a bit tricky in the real world.

The ekf_node we will configure in this tutorial will subscribe to the following topics (ROS message types are in parentheses):

- /mecanum_drive_controller/odom (nav_msgs/Odometry)

- /imu/data (sensor_msgs/Imu.msg)

This node will publish data to the following topics:

- /odometry/filtered : The smoothed odometry information (nav_msgs/Odometry) generated by fusing the IMU and wheel odometry data.

- /tf : Coordinate transform from the odom frame (parent) to the base_footprint frame (child).

Configure Robot Localization

We need to specify the configuration parameters of the ekf_node by creating a YAML file. Your friend for configuring the robot_localization package for your robot is the official documentation at this website.

Let’s get into it!

Open a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_localization/mkdir -p config && cd configtouch ekf.yamlAdd this code inside this file:

### ekf config file ###

ekf_filter_node:

ros__parameters:

# The frequency, in Hz, at which the filter will output a position estimate. Note that the filter will not begin

# computation until it receives at least one message from one of the inputs. It will then run continuously at the

# frequency specified here, regardless of whether it receives more measurements. Defaults to 30 if unspecified.

frequency: 15.0

# ekf_localization_node and ukf_localization_node both use a 3D omnidirectional motion model. If this parameter is

# set to true, no 3D information will be used in your state estimate. Use this if you are operating in a planar

# environment and want to ignore the effect of small variations in the ground plane that might otherwise be detected

# by, for example, an IMU. Defaults to false if unspecified.

two_d_mode: true

# Whether to broadcast the transformation over the /tf topic. Defaults to true if unspecified.

publish_tf: true

# REP-105 (http://www.ros.org/reps/rep-0105.html) specifies four principal coordinate frames: base_link, odom, map, and

# earth. base_link is the coordinate frame that is affixed to the robot. Both odom and map are world-fixed frames.

# The robot's position in the odom frame will drift over time, but is accurate in the short term and should be

# continuous. The odom frame is therefore the best frame for executing local motion plans. The map frame, like the odom

# frame, is a world-fixed coordinate frame, and while it contains the most globally accurate position estimate for your

# robot, it is subject to discrete jumps, e.g., due to the fusion of GPS data or a correction from a map-based

# localization node. The earth frame is used to relate multiple map frames by giving them a common reference frame.

# ekf_localization_node and ukf_localization_node are not concerned with the earth frame.

# Here is how to use the following settings:

# 1. Set the map_frame, odom_frame, and base_link frames to the appropriate frame names for your system.

# 1a. If your system does not have a map_frame, just remove it, and make sure "world_frame" is set to the value of

# odom_frame.

# 2. If you are fusing continuous position data such as wheel encoder odometry, visual odometry, or IMU data, set

# "world_frame" to your odom_frame value. This is the default behavior for robot_localization's state estimation nodes.

# 3. If you are fusing global absolute position data that is subject to discrete jumps (e.g., GPS or position updates

# from landmark observations) then:

# 3a. Set your "world_frame" to your map_frame value

# 3b. MAKE SURE something else is generating the odom->base_link transform. Note that this can even be another state

# estimation node from robot_localization! However, that instance should *not* fuse the global data.

map_frame: map # Defaults to "map" if unspecified

odom_frame: odom # Defaults to "odom" if unspecified

base_link_frame: base_footprint # Defaults to "base_link" if unspecified

world_frame: odom # Defaults to the value of odom_frame if unspecified

# The filter accepts an arbitrary number of inputs from each input message type (nav_msgs/Odometry,

# geometry_msgs/PoseWithCovarianceStamped, geometry_msgs/TwistWithCovarianceStamped,

# sensor_msgs/Imu). To add an input, simply append the next number in the sequence to its "base" name, e.g., odom0,

# odom1, twist0, twist1, imu0, imu1, imu2, etc. The value should be the topic name. These parameters obviously have no

# default values, and must be specified.

odom0: mecanum_drive_controller/odom

# Each sensor reading updates some or all of the filter's state. These options give you greater control over which

# values from each measurement are fed to the filter. For example, if you have an odometry message as input, but only

# want to use its Z position value, then set the entire vector to false, except for the third entry. The order of the

# values is x, y, z, roll, pitch, yaw, vx, vy, vz, vroll, vpitch, vyaw, ax, ay, az. Note that not some message types

# do not provide some of the state variables estimated by the filter. For example, a TwistWithCovarianceStamped message

# has no pose information, so the first six values would be meaningless in that case. Each vector defaults to all false

# if unspecified, effectively making this parameter required for each sensor.

odom0_config: [false, false, false,

false, false, false,

true, true, false,

false, false, true,

false, false, false]

# [x_pos , y_pos , z_pos,

# roll , pitch , yaw,

# x_vel , y_vel , z_vel,

# roll_vel, pitch_vel, yaw_vel,

# x_accel , y_accel , z_accel]

imu0: imu/data

imu0_config: [false, false, false,

false, false, false,

false, false, false,

false, false, true,

true, true, false]

Let’s walk through this file together.

First, let’s talk about the frequency parameter. This parameter determines how often the filter provides updated location data. In our case, it’s set to 15 Hz, which means the robot gets a new position estimate 15 times every second.

Next, we have the two_d_mode setting. By setting this to true, we’re telling the filter to focus only on the robot’s position in a flat, two-dimensional plane. This means it will ignore any small up and down movements, which is perfect for our robot since it has mecanum wheels that allow it to move smoothly on a flat surface.

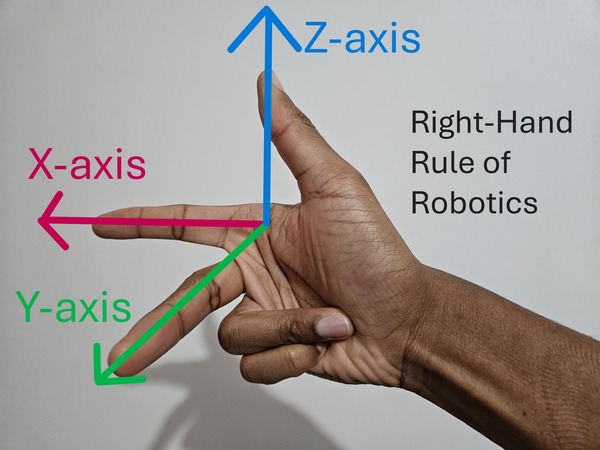

Now, let’s discuss coordinate frames. The configuration file specifies three main frames: map_frame, odom_frame, and base_link_frame. These frames help the robot understand its location from different perspectives.

The map_frame represents the robot’s position in the overall environment.

The odom_frame tracks the robot’s movement from its starting point

I like to set the base_link_frame to the base_footprint.

The world_frame is a special coordinate frame that serves as a reference for the other frames. In the configuration file, it’s set to the same value as the odom_frame. This means that the robot’s odometry frame, which tracks its movement from its starting point, is being used as the reference frame for the entire system.

Using the odom_frame as the world_frame is a common practice when the robot is primarily relying on continuous position data from sources like wheel encoders, visual odometry, or IMU data. By setting the world_frame to the odom_frame, we’re essentially telling the robot that its odometry data is the most reliable source for tracking its overall position and movement.

However, there are cases where you might want to set the world_frame to the map_frame instead. This is typically done when the robot is using global absolute position data that may be subject to sudden jumps or corrections, such as GPS data or position updates from recognizing landmarks. In such cases, setting the world_frame to the map_frame helps the robot maintain a more accurate global position estimate.

To estimate the robot’s position and movement, the ekf_filter_node needs data from the robot’s sensors. This is where the odom0 and imu0 parameters come into play.

odom0 refers to the wheel odometry data, which is used to estimate the robot’s velocity in the x and y directions, as well as its rotation speed around the vertical axis (yaw). The odom0_config parameter specifies which aspects of the odometry data should be used by the filter.

Similarly, imu0 refers to the data from the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which provides information about the robot’s acceleration and rotation. The imu0_config parameter defines which aspects of the IMU data should be used by the filter.

By putting all these settings together in the configuration file, we give our robot the tools it needs to understand its position and movement as it navigates through its environment on its mecanum wheels. This setup enables the robot to perform tasks more effectively and safely, as it has a clear understanding of its location and how it is moving.

Create Launch Files

Now let’s create a launch file.

Open up a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_localization/mkdir -p launch/ && cd launchtouch ekf_gazebo.launch.pyAdd this code.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Launch file for the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) node in Gazebo simulation.

This script starts the robot_localization package's EKF node which combines (fuses)

data from wheel odometry and IMU sensors to better estimate the robot's position

and orientation.

:author: Addison Sears-Collins

:date: November 29, 2024

"""

import os

from launch import LaunchDescription

from launch.actions import DeclareLaunchArgument

from launch.substitutions import LaunchConfiguration

from launch_ros.actions import Node

from launch_ros.substitutions import FindPackageShare

def generate_launch_description():

"""

Generate a launch description for the EKF node.

This function creates and returns a LaunchDescription object that will start

the EKF node from the robot_localization package. The node is configured

using parameters from a YAML file.

Returns:

LaunchDescription: A complete launch description for the EKF node

"""

# Constants for paths to different files and folders

package_name = 'yahboom_rosmaster_localization'

# Config file paths

ekf_config_file_path = 'config/ekf.yaml'

# Set the path to different packages

pkg_share = FindPackageShare(package=package_name).find(package_name)

# Set the path to config files

default_ekf_config_path = os.path.join(pkg_share, ekf_config_file_path)

# Launch configuration variables

ekf_config_file = LaunchConfiguration('ekf_config_file')

use_sim_time = LaunchConfiguration('use_sim_time')

# Declare the launch arguments

declare_ekf_config_file_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='ekf_config_file',

default_value=default_ekf_config_path,

description='Full path to the EKF configuration YAML file'

)

declare_use_sim_time_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='use_sim_time',

default_value='true',

description='Use simulation (Gazebo) clock if true'

)

# Specify the actions

start_ekf_node_cmd = Node(

package='robot_localization',

executable='ekf_node',

name='ekf_filter_node',

output='screen',

parameters=[

ekf_config_file,

{'use_sim_time': use_sim_time}

]

)

# Create the launch description and populate

ld = LaunchDescription()

# Add the declarations

ld.add_action(declare_ekf_config_file_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_use_sim_time_cmd)

# Add the actions

ld.add_action(start_ekf_node_cmd)

return ld

Save the file, and close it.

Open up a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_bringup/launchtouch rosmaster_x3_navigation.launch.pyAdd this code.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

Launch Nav2 for the Yahboom ROSMASTER X3 robot in Gazebo.

This launch file sets up a complete ROS 2 navigation environment.

:author: Addison Sears-Collins

:date: November 29, 2024

"""

import os

from launch import LaunchDescription

from launch.actions import DeclareLaunchArgument, IncludeLaunchDescription

from launch.launch_description_sources import PythonLaunchDescriptionSource

from launch.substitutions import LaunchConfiguration

from launch_ros.substitutions import FindPackageShare

def generate_launch_description():

"""

Generate a launch description.

Returns:

LaunchDescription: A complete launch description for the robot.

"""

# Constants for paths to different packages

package_name_gazebo = 'yahboom_rosmaster_gazebo'

package_name_localization = 'yahboom_rosmaster_localization'

# Launch and config file paths

gazebo_launch_file_path = 'launch/yahboom_rosmaster.gazebo.launch.py'

ekf_launch_file_path = 'launch/ekf_gazebo.launch.py'

ekf_config_file_path = 'config/ekf.yaml'

rviz_config_file_path = 'rviz/yahboom_rosmaster_gazebo_sim.rviz'

# Set the path to different packages

pkg_share_gazebo = FindPackageShare(package=package_name_gazebo).find(package_name_gazebo)

pkg_share_localization = FindPackageShare(

package=package_name_localization).find(package_name_localization)

# Set default paths

default_gazebo_launch_path = os.path.join(pkg_share_gazebo, gazebo_launch_file_path)

default_ekf_launch_path = os.path.join(pkg_share_localization, ekf_launch_file_path)

default_ekf_config_path = os.path.join(pkg_share_localization, ekf_config_file_path)

default_rviz_config_path = os.path.join(pkg_share_gazebo, rviz_config_file_path)

# Launch configuration variables

# Config and launch files

enable_odom_tf = LaunchConfiguration('enable_odom_tf')

ekf_config_file = LaunchConfiguration('ekf_config_file')

ekf_launch_file = LaunchConfiguration('ekf_launch_file')

gazebo_launch_file = LaunchConfiguration('gazebo_launch_file')

rviz_config_file = LaunchConfiguration('rviz_config_file')

# Robot configuration

robot_name = LaunchConfiguration('robot_name')

world_file = LaunchConfiguration('world_file')

# Position and orientation

x = LaunchConfiguration('x')

y = LaunchConfiguration('y')

z = LaunchConfiguration('z')

roll = LaunchConfiguration('roll')

pitch = LaunchConfiguration('pitch')

yaw = LaunchConfiguration('yaw')

# Feature flags

headless = LaunchConfiguration('headless')

jsp_gui = LaunchConfiguration('jsp_gui')

load_controllers = LaunchConfiguration('load_controllers')

use_gazebo = LaunchConfiguration('use_gazebo')

use_robot_state_pub = LaunchConfiguration('use_robot_state_pub')

use_rviz = LaunchConfiguration('use_rviz')

use_sim_time = LaunchConfiguration('use_sim_time')

# Declare all launch arguments

# Config and launch files

declare_ekf_config_file_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='ekf_config_file',

default_value=default_ekf_config_path,

description='Full path to the EKF configuration YAML file')

declare_ekf_launch_file_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='ekf_launch_file',

default_value=default_ekf_launch_path,

description='Full path to the EKF launch file to use')

declare_enable_odom_tf_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='enable_odom_tf',

default_value='true',

choices=['true', 'false'],

description='Whether to enable odometry transform broadcasting via ROS 2 Control')

declare_gazebo_launch_file_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='gazebo_launch_file',

default_value=default_gazebo_launch_path,

description='Full path to the Gazebo launch file to use')

declare_rviz_config_file_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='rviz_config_file',

default_value=default_rviz_config_path,

description='Full path to the RVIZ config file to use')

# Robot configuration

declare_robot_name_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='robot_name',

default_value='rosmaster_x3',

description='The name for the robot')

declare_world_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='world_file',

default_value='empty.world',

description='World file name (e.g., empty.world, house.world)')

# Position arguments

declare_x_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='x',

default_value='0.0',

description='x component of initial position, meters')

declare_y_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='y',

default_value='0.0',

description='y component of initial position, meters')

declare_z_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='z',

default_value='0.05',

description='z component of initial position, meters')

# Orientation arguments

declare_roll_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='roll',

default_value='0.0',

description='roll angle of initial orientation, radians')

declare_pitch_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='pitch',

default_value='0.0',

description='pitch angle of initial orientation, radians')

declare_yaw_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='yaw',

default_value='0.0',

description='yaw angle of initial orientation, radians')

# Feature flags

declare_headless_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='headless',

default_value='False',

description='Whether to execute gzclient (visualization)')

declare_jsp_gui_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='jsp_gui',

default_value='false',

description='Flag to enable joint_state_publisher_gui')

declare_load_controllers_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='load_controllers',

default_value='true',

description='Flag to enable loading of ROS 2 controllers')

declare_use_gazebo_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='use_gazebo',

default_value='true',

description='Flag to enable Gazebo')

declare_use_robot_state_pub_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='use_robot_state_pub',

default_value='true',

description='Flag to enable robot state publisher')

declare_use_rviz_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='use_rviz',

default_value='true',

description='Flag to enable RViz')

declare_use_sim_time_cmd = DeclareLaunchArgument(

name='use_sim_time',

default_value='true',

description='Use simulation (Gazebo) clock if true')

# Specify the actions

# Start Gazebo

start_gazebo_cmd = IncludeLaunchDescription(

PythonLaunchDescriptionSource([gazebo_launch_file]),

launch_arguments={

'enable_odom_tf': enable_odom_tf,

'headless': headless,

'jsp_gui': jsp_gui,

'load_controllers': load_controllers,

'robot_name': robot_name,

'rviz_config_file': rviz_config_file,

'use_rviz': use_rviz,

'use_gazebo': use_gazebo,

'use_robot_state_pub': use_robot_state_pub,

'use_sim_time': use_sim_time,

'world_file': world_file,

'x': x,

'y': y,

'z': z,

'roll': roll,

'pitch': pitch,

'yaw': yaw

}.items()

)

# Start EKF

start_ekf_cmd = IncludeLaunchDescription(

PythonLaunchDescriptionSource([ekf_launch_file]),

launch_arguments={

'ekf_config_file': ekf_config_file,

'use_sim_time': use_sim_time

}.items()

)

# Create the launch description and populate

ld = LaunchDescription()

# Add all launch arguments

# Config and launch files

ld.add_action(declare_enable_odom_tf_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_ekf_config_file_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_ekf_launch_file_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_gazebo_launch_file_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_rviz_config_file_cmd)

# Robot configuration

ld.add_action(declare_robot_name_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_world_cmd)

# Position declarations

ld.add_action(declare_x_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_y_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_z_cmd)

# Orientation declarations

ld.add_action(declare_roll_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_pitch_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_yaw_cmd)

# Feature flags

ld.add_action(declare_headless_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_jsp_gui_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_load_controllers_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_use_gazebo_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_use_robot_state_pub_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_use_rviz_cmd)

ld.add_action(declare_use_sim_time_cmd)

# Add any actions

ld.add_action(start_ekf_cmd)

ld.add_action(start_gazebo_cmd)

return ld

Save the file, and close it.

Open up a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_bringup/scripts/touch rosmaster_x3_navigation.shAdd this code.

#!/bin/bash

# Single script to launch the Yahboom ROSMASTERX3 with Gazebo, Nav2 and ROS 2 Controllers

cleanup() {

echo "Cleaning up..."

sleep 5.0

pkill -9 -f "ros2|gazebo|gz|nav2|amcl|bt_navigator|nav_to_pose|rviz2|assisted_teleop|cmd_vel_relay|robot_state_publisher|joint_state_publisher|move_to_free|mqtt|autodock|cliff_detection|moveit|move_group|basic_navigator"

}

# Set up cleanup trap

trap 'cleanup' SIGINT SIGTERM

# For cafe.world -> z:=0.20

# For house.world -> z:=0.05

# To change Gazebo camera pose: gz service -s /gui/move_to/pose --reqtype gz.msgs.GUICamera --reptype gz.msgs.Boolean --timeout 2000 --req "pose: {position: {x: 0.0, y: -2.0, z: 2.0} orientation: {x: -0.2706, y: 0.2706, z: 0.6533, w: 0.6533}}"

echo "Launching Gazebo simulation with Nav2..."

ros2 launch yahboom_rosmaster_bringup rosmaster_x3_navigation.launch.py \

enable_odom_tf:=false \

headless:=False \

load_controllers:=true \

world_file:=cafe.world \

use_rviz:=true \

use_robot_state_pub:=true \

use_sim_time:=true \

x:=0.0 \

y:=0.0 \

z:=0.20 \

roll:=0.0 \

pitch:=0.0 \

yaw:=0.0 &

echo "Waiting 25 seconds for simulation to initialize..."

sleep 25

echo "Adjusting camera position..."

gz service -s /gui/move_to/pose --reqtype gz.msgs.GUICamera --reptype gz.msgs.Boolean --timeout 2000 --req "pose: {position: {x: 0.0, y: -2.0, z: 2.0} orientation: {x: -0.2706, y: 0.2706, z: 0.6533, w: 0.6533}}"

# Keep the script running until Ctrl+C

wait

Save the file, and close it.

Add RViz Configuration File

Open up a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_navigation/mkdir -p rviz && cd rviztouch nav2_default_view.rvizAdd this code.

Save the file, and close it.

Add Aliases

Let’s add an alias to make launching all this much easier.

Open the .bashrc file

gedit ~/.bashrcScroll to the bottom of the file or look for a section with other alias definitions.

Add this line:

alias nav='bash ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_bringup/scripts/rosmaster_x3_navigation.sh'Save the file, and close it.

Edit the ROS Bridge Configuration YAML File

To make the robot localization package work with Gazebo, we need to send the clock data from Gazebo over to ROS 2.

Open up a new terminal window, and type:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_gazebo/config/Open ros_gz_bridge.yaml.

Add this code.

# Clock configuration

- ros_topic_name: "clock"

gz_topic_name: "clock"

ros_type_name: "rosgraph_msgs/msg/Clock"

gz_type_name: "gz.msgs.Clock"

direction: GZ_TO_ROS

lazy: false

Save the file, and close it.

Edit CMakeLists.txt

Open a terminal and navigate to the yahboom_rosmaster_localization package directory:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_localization/Open the CMakeLists.txt file.

Add the following lines to the file:

install (

DIRECTORY config launch

DESTINATION share/${PROJECT_NAME}

)

Save the file, and close it.

Open a terminal and navigate to the yahboom_rosmaster_navigation package directory:

cd ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_navigation/Open the CMakeLists.txt file.

Add the following lines to the file:

install (

DIRECTORY rviz

DESTINATION share/${PROJECT_NAME}

)

Save the file, and close it.

Build the Package

Now we will build the package.

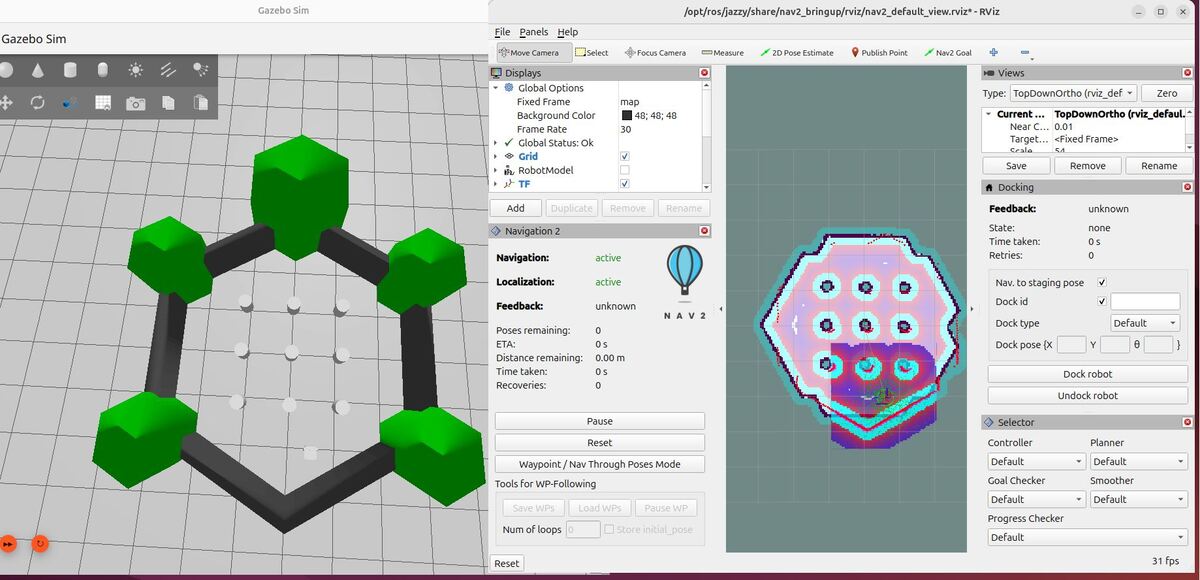

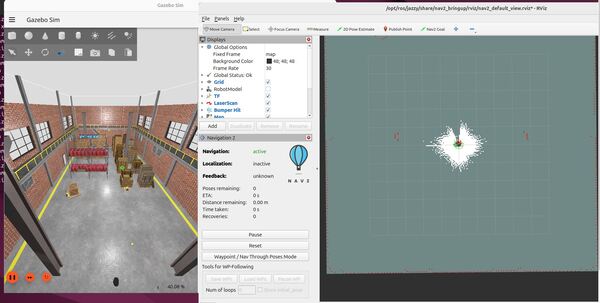

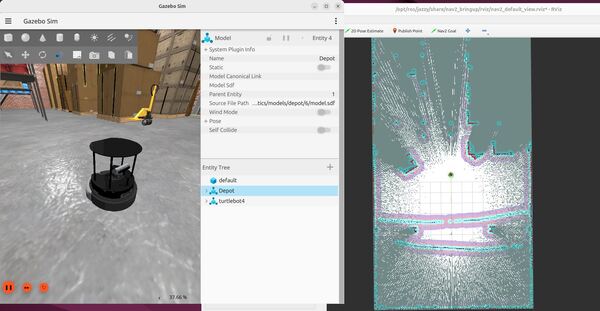

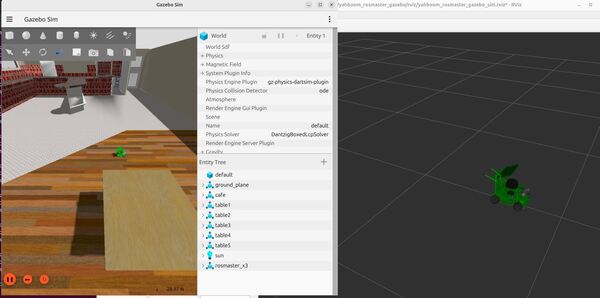

cd ~/ros2_ws/colcon build && source ~/.bashrcLaunch the Robot

Let’s bring our robot to life. Open a terminal window, and use this command to launch the robot:

navor

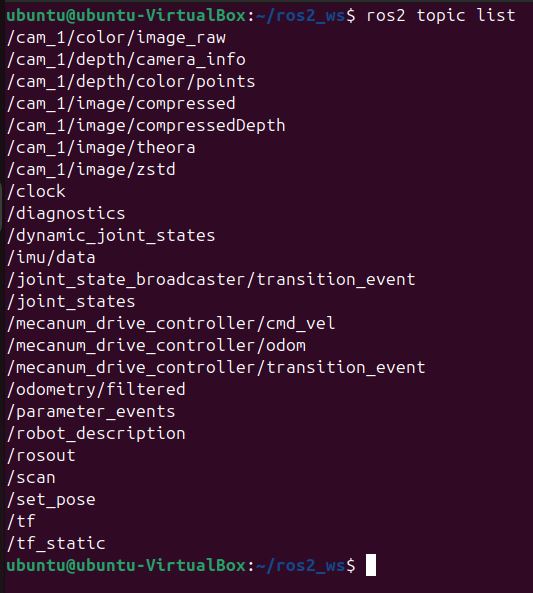

bash ~/ros2_ws/src/yahboom_rosmaster/yahboom_rosmaster_bringup/scripts/rosmaster_x3_navigation.shTo see the active topics, open a terminal window, and type:

ros2 topic list

To see more information about the topics, execute:

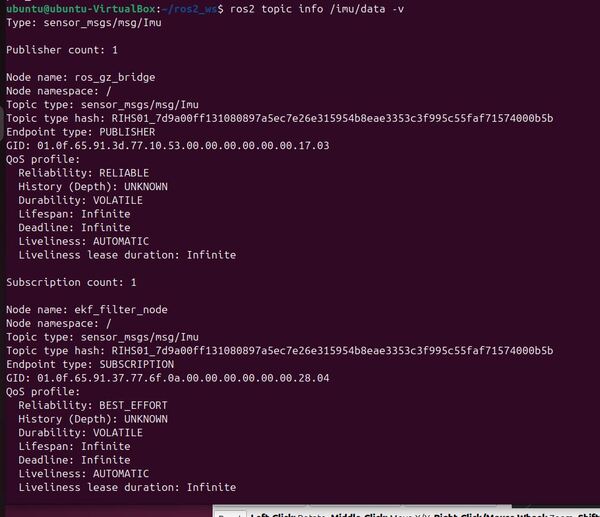

ros2 topic info /imu/data -v

To see the data type:

ros2 topic echo /imu/dataNow check out the wheel odometry:

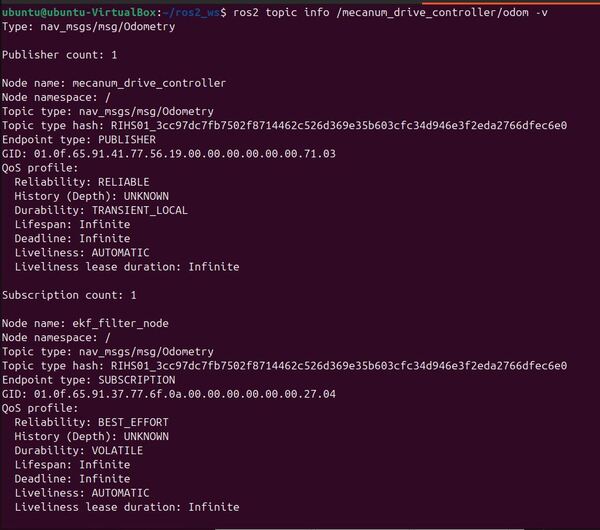

ros2 topic info /mecanum_drive_controller/odom -v

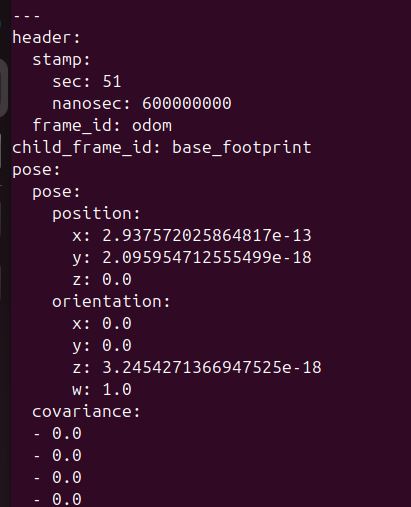

ros2 topic echo /mecanum_drive_controller/odom

Make sure the timestamp on the topic indicates simulation time.

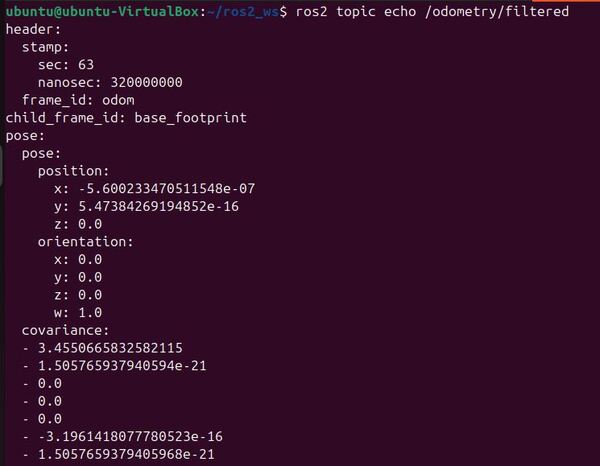

To see the output of the robot localization package (i.e. the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)), type:

ros2 topic echo /odometry/filtered

Make sure the timestamp on this odometry topic indicates simulation time.

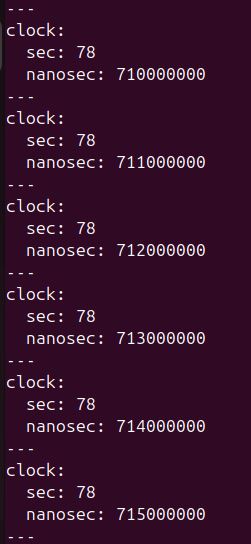

Let’s see the simulation time:

ros2 topic echo /clock

This clock data is coming from Gazebo via the ROS 2 Gazebo bridge YAML file we configured earlier in this tutorial.

I will move my robot around in a square shaped pattern:

ros2 run yahboom_rosmaster_system_tests square_mecanum_controller --ros-args -p use_sim_time:=true

Remember we need to set use_sim_time to true in the command above so that the node gets the time from the /clock ROS 2 topic rather than the system time.

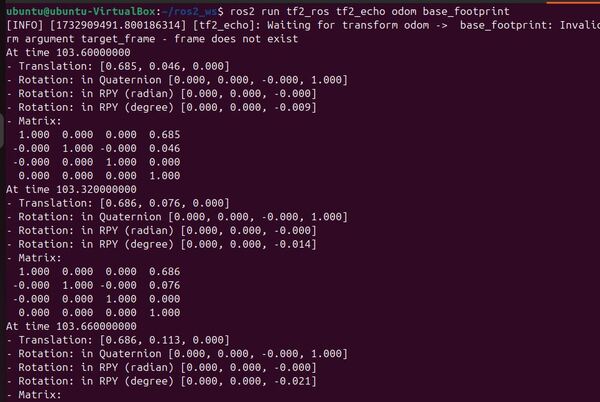

We can see the output of the odom -> base_footprint transform by typing the following command:

ros2 run tf2_ros tf2_echo odom base_footprint

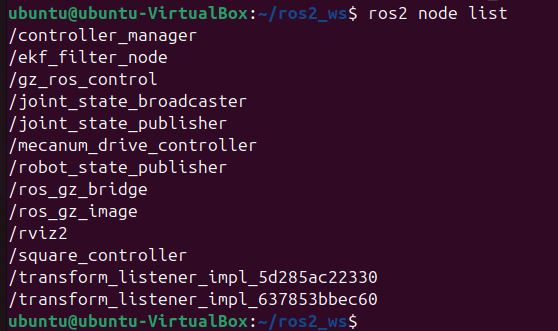

Let’s see the active nodes.

ros2 node list

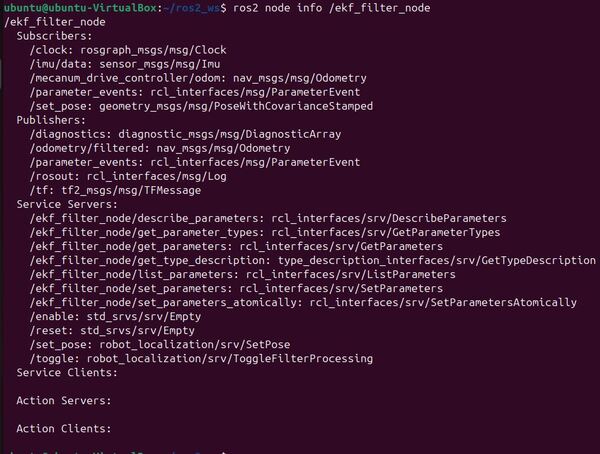

Let’s check out the ekf_node (named ekf_filter_node).

ros2 node info /ekf_filter_node

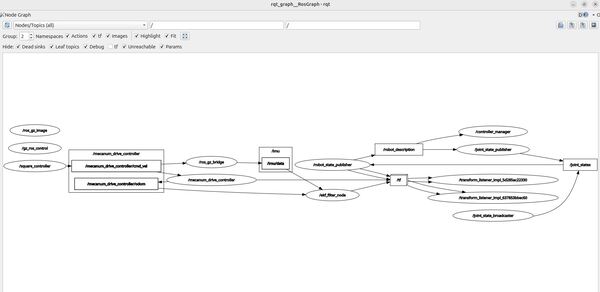

Let’s check out the ROS node graph.

rqt_graphClick the blue circular arrow in the upper left to refresh the node graph. Also select “Nodes/Topics (all)”.

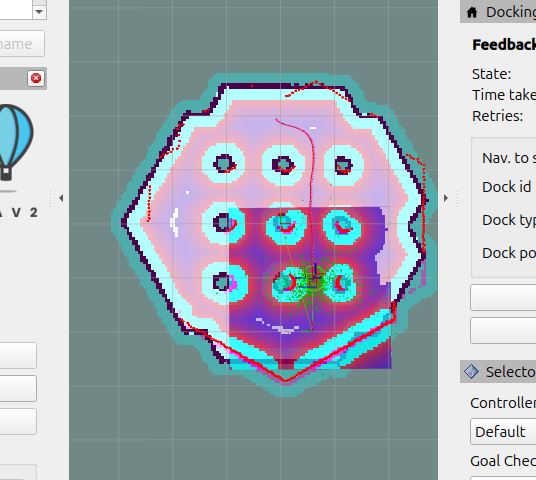

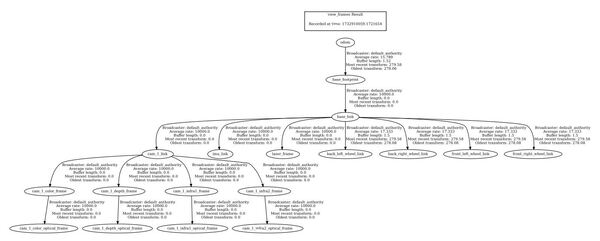

To see the coordinate frames, type the following command in a terminal window.

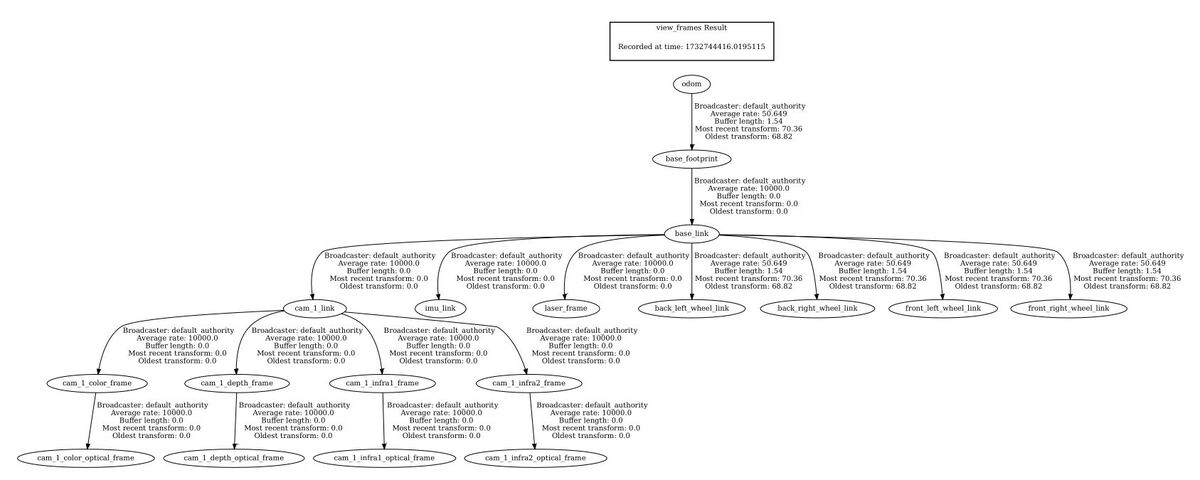

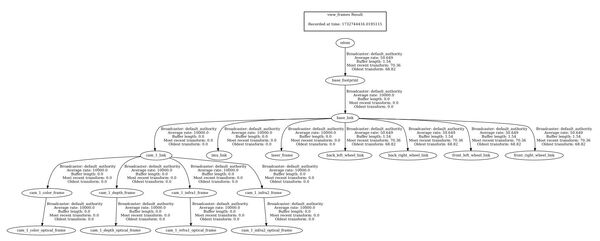

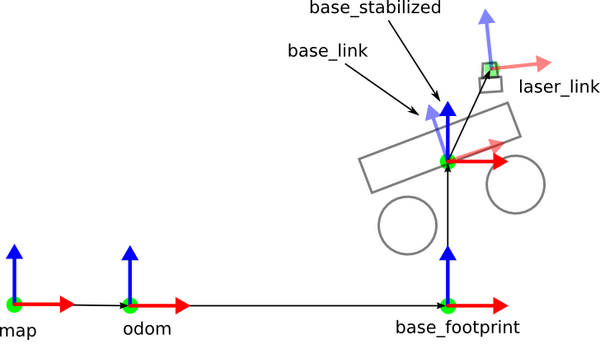

cd ~/Downloads/ros2 run tf2_tools view_framesIn the current working directory, you will have a file called frames_20XX.pdf. Open that file.

evince frames_20XX.pdfHere is what my coordinate transform (i.e. tf) tree looks like:

You can see that the parent frame is the odom frame. The odom frame is the initial position and orientation of the robot. Every other frame below that is a child of the odom frame.

Later, we will add a map frame. The map frame will be the parent frame of the odom frame.

That’s it! Keep building!