In this post, we will learn how to create and execute publisher and subscriber nodes in ROS using C++ and Python.

A node in ROS is just a program (e.g. typically a piece of source code made in C++ or Python) that does some computation. ROS nodes reside inside ROS packages. ROS packages reside inside the src folder of your catkin workspace (i.e. catkin_ws).

Table of Contents

- How to Create a Publisher Node in ROS Using C++

- How to Create a Subscriber Node in ROS Using C++

- How to Create the Executable for ROS C++ Nodes

- How to Create a Publisher Node in ROS Using Python

- How to Create a Subscriber Node in ROS Using Python

- How to Execute ROS Python Nodes

Directions

How to Create a Publisher Node in ROS Using C++

If you don’t already have a package named “hello_world” set up, set that up now.

Once you have your package set up, you are ready to create a node. Let’s create our first node. This node will be a publisher node. A publisher node is a software program that publishes messages (i.e. data values) to a particular topic. Check out this post, if you need more clarification on what a publisher and a topic are.

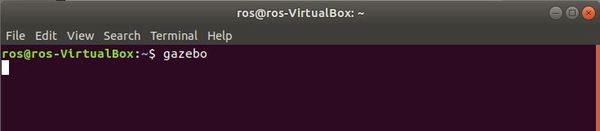

Open up a new Linux terminal window.

Type the following command to open the Linux text editor.

gedit

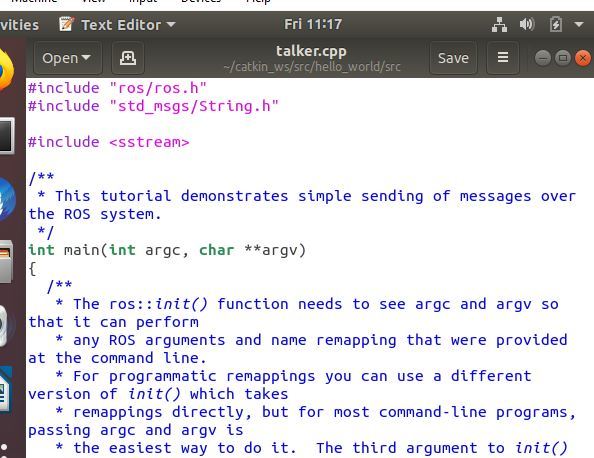

Insert the C++ code at this link at the ROS.org website into the text file. To understand what each piece of the code does, read this link.

Save the file as talker.cpp in your catkin_ws/src/hello_world/src folder and close the window.

That’s all there is to it. Now, let’s create a subscriber node.

How to Create a Subscriber Node in ROS Using C++

We now need a program that subscribes to the data (i.e. “hello world” message) published by the talker. This node will be a subscriber node. A subscriber node is a software program that subscribes to messages (i.e. data values) on a particular topic.

Open up a new Linux terminal window.

Type the following command to open the Linux text editor.

gedit

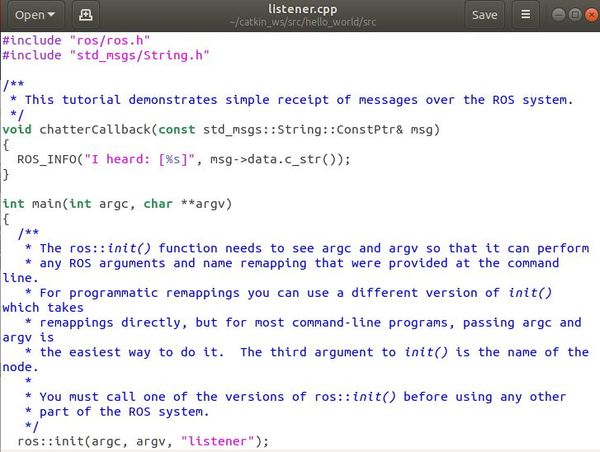

Insert the C++ code at this link at the ROS.org website into the text file. To understand what each piece of the code does, read this link.

Save the file as listener.cpp in your catkin_ws/src/hello_world/src folder and close the window.

You’re all set. Now, let’s create the executable.

How to Create the Executable for ROS C++ Nodes

Our two nodes have been created, but now we need to convert that source code written in C++ into an executable that our machine can understand. To do that, open a new terminal window, and navigate to your catkin_ws/src/hello_world/ folder.

cd catkin_ws/src/hello_world/

Type the dir command to see the list of files in that directory. One of these files is CMakeLists.txt. Open that file.

gedit CMakeLists.txt

Add these lines to the very bottom of your CMakeLists.txt file.

add_executable(talker src/talker.cpp)

target_link_libraries(talker ${catkin_LIBRARIES})

add_executable(listener src/listener.cpp)

target_link_libraries(listener ${catkin_LIBRARIES})

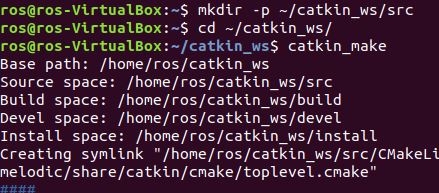

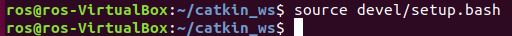

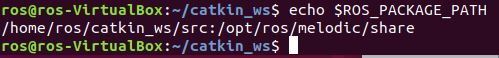

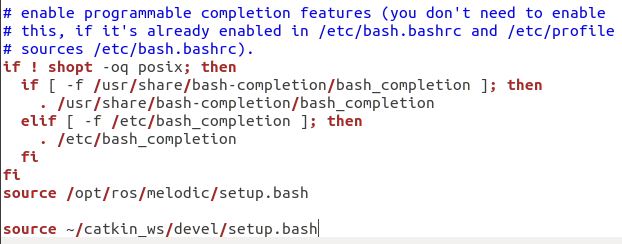

Move to the catkin_ws folder.

cd ~/catkin_ws

Build the nodes.

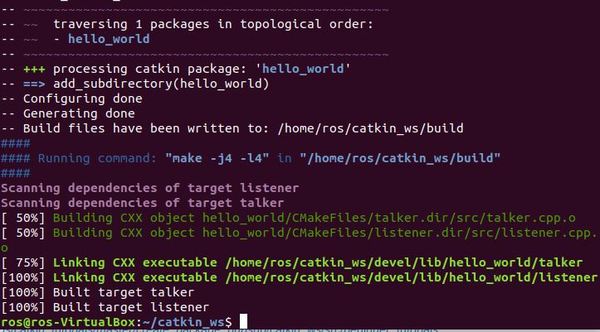

catkin_make

You should see a screen that look something like the image below, indicating that the executables were successfully built.

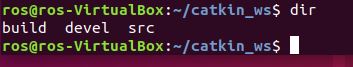

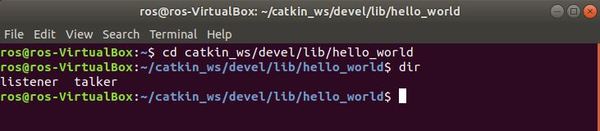

Now, open a new terminal window and go to the catkin_ws/devel/lib/hello_world/ folder.

cd catkin_ws/devel/lib/hello_world

Type dir to see the files listed. You will see the listener and talker executables. Feel free to close the terminal window now.

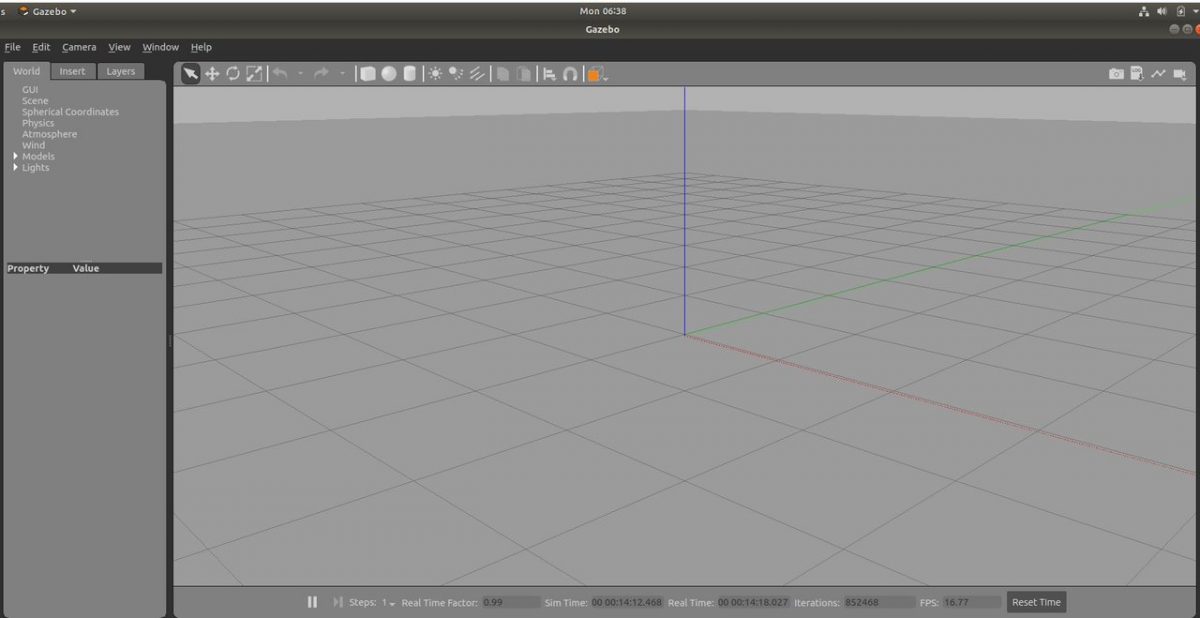

Let’s execute the nodes. To do that, in a fresh terminal window launch ROS by typing:

roscore

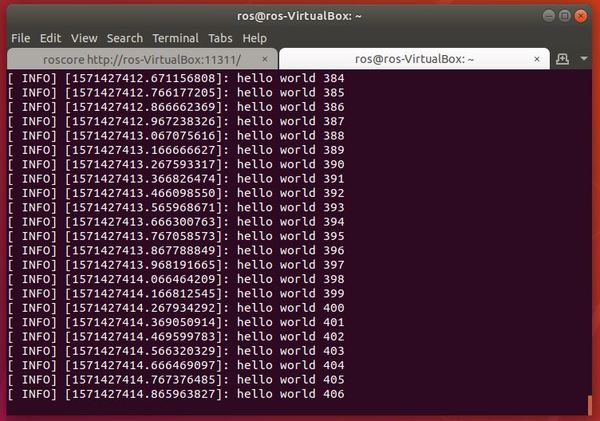

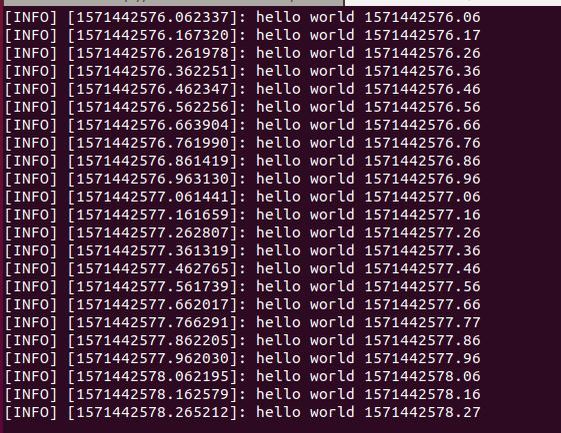

In another window, start the talker node (i.e. Publisher Node) by typing:

rosrun hello_world talker

You should see numbered “hello world” messages printing to the screen.

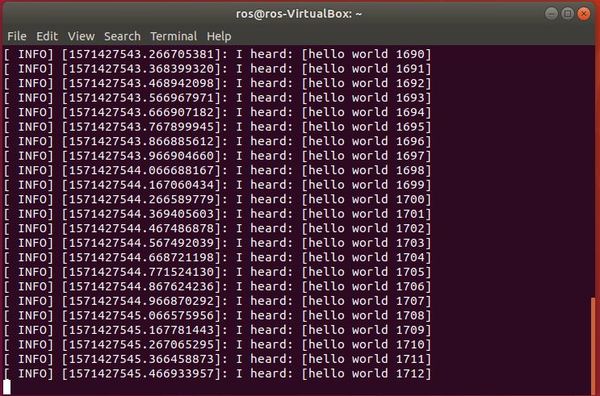

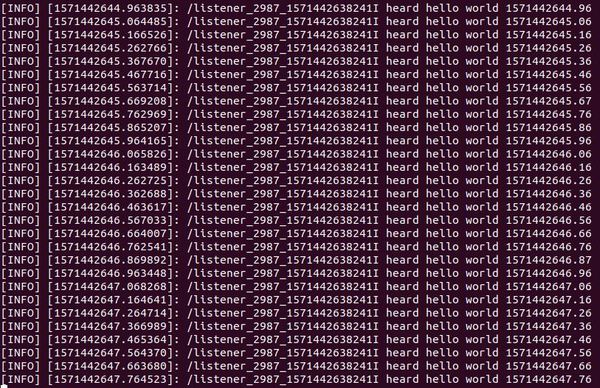

Now, let’s start the listener node (Subscriber Node). Open a new terminal window, and type:

rosrun hello_world listener

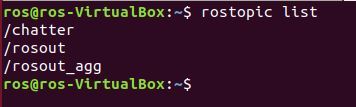

Finally, let’s see what ROS topics are currently active. In a new terminal window, type:

rostopic list

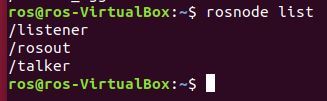

Let’s get a list of the nodes that are currently active.

rosnode list

Press CTRL+C at any time to stop the program from running.

How to Create a Publisher Node in ROS Using Python

Now that we’ve seen how we can create publisher and subscriber nodes using C++, let’s do the same thing using Python.

Open up a new Linux terminal window.

Type the following command to open the Linux text editor.

gedit

Insert the Python code at this link at the ROS.org website into the text file. To understand what each piece of the code does, read this link.

Save the file as talker.py in your catkin_ws/src/hello_world/scripts folder and close the window.

How to Create a Subscriber Node in ROS Using Python

Open up a new Linux terminal window.

Type the following command to open the Linux text editor.

gedit

Insert the Python code at this link at the ROS.org website into the text file. To understand what each piece of the code does, read this link.

Save the file as listener.py in your catkin_ws/src/hello_world/scripts folder and close the window.

How to Execute ROS Python Nodes

Open up a new terminal window.

Navigate to the catkin_ws/src/hello_world/scripts folder.

cd catkin_ws/src/hello_world/scripts

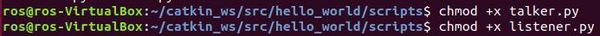

Make the files executable. Type each command twice, pressing Enter after each.

chmod +x talker.py

chmod +x talker.py

chmod +x listener.py

chmod +x listener.py

In a new terminal window, launch ROS.

roscore

Open a new terminal window, and execute talker.py.

rosrun hello_world talker.py

Open another terminal window and type:

rosrun hello_world listener.py

To stop the program, type CTRL+C.

A cool ROS command that you can use at any time to see a list of active nodes is the following:

rosnode list

To find out information about the node, type the following command:

rosnode info /[name of node]

Congratulations! We have covered a lot of ground. You now know how to build publisher and subscriber nodes using the two most common languages used in robotics, Python and C++.