In this tutorial, we will create a Python publisher for ROS 2. Knowing how to write a publisher node is one of the most important skills in robotics software engineering.

In ROS 2 (Robot Operating System 2), a Python publisher is a script written in Python that sends messages across the ROS network to other parts of the system.

On a real robot, you will write many different publishers that publish data that gets shared by the different components of a robot: strings, LIDAR scan readings, ultrasonic sensor readings, camera frames, 3D point cloud data, integers, float values, battery voltage readings, odometry data, and much more.

The official instructions for creating a publisher are here, but I will walk you through the entire process, step by step.

Follow along with me click by click, keystroke by keystroke.

We will be following the ROS 2 Python Style Guide.

Let’s get started!

Prerequisites

- You have completed this tutorial: How to Create a ROS 2 Package – Jazzy.

- I am assuming you are using Visual Studio Code, but you can use any code editor.

Understand Important ROS 2 Vocabulary

Before we write our first publisher node, let’s understand some ROS 2 vocabulary.

What Are Publisher Nodes?

In a complex robot, you are going to have many pieces of code in your system that need to communicate with each other.

For example, the code that is responsible for making navigation decisions needs to subscribe to laser scan messages from the LIDAR to be able to avoid obstacles properly.

You might have another piece of code that reads from the robot’s battery and publishes the percentage battery remaining.

In ROS 2, the parts of your system that are responsible for publishing messages to the rest of the robot – like the distance to an obstacle – are known as publisher nodes. These nodes are usually written in C++ and Python.

You have many different types of built-in messages that you can publish over ROS 2.

For example, if you want to send distance information from a LIDAR sensor, you have a special sensor message called LaserScan. You can see the definition of this message type on this link.

For battery health, you even have a special sensor message type for that called BatteryState.

You also have other sensor message types, which you can see on this list.

In a previous tutorial, we published the text message “Hello World” from a publisher node called talker. This message type is a string, which is one of the standard message types in ROS 2.

On this link, you can see we have standard message types for integers, floating-point numbers, booleans (like True and False), and many more.

The beauty of ROS 2 is that there is a message type for 95% of robotic scenarios. For the other 5%, you can create your own custom message type. I will show you how to do that in a future tutorial.

What Are Subscriber Nodes?

The parts of your system that subscribe to messages sent from publishers are known as subscriber nodes.

Subscriber nodes are pieces of code, usually written in C++ or Python, that are responsible for receiving information.

For example, the robot’s path planning code could be a subscriber node since it subscribes to LIDAR data to plan a collision-free path from an initial location to a goal location.

What Are Messages?

Messages are the data packets that the publisher nodes send out. They can include information like LIDAR scan data, camera images, ultrasonic sensor readings, numbers, text, or even complex data structures.

You can find a master list of the different types of messages by going here to the ROS 2 documentation. You even have other message types to represent things like bounding boxes for object detection.

What Are Topics?

Topics are the named channels over which messages are sent out.

For example, in many real-world mobile robotics applications where you are using a LIDAR, messages about the distance to obstacles are sent on a topic named “/scan”. By convention, the name of a topic in ROS 2 has a leading forward slash before the name.

Topics allow different parts of a robot or rather different nodes in a robotic system to communicate with each other by subscribing to and publishing messages on these named channels.

Write the Code

Now that we have covered some fundamental terminology, let’s write some code.

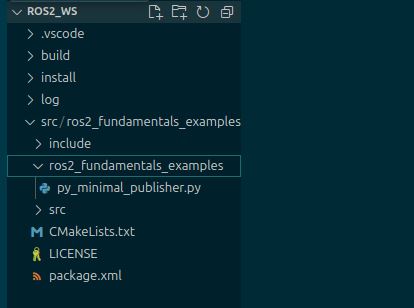

cd ~/ros2_ws/ && code .First, right-click on src/ros2_fundamentals/

Type “ros2_fundamentals_examples” to create a new folder for our Python script.

Pay careful attention to the name of the folder where we will house our Python scripts. The name of this folder must have the same name as the package.

Right-click on the ros2_fundamentals_examples folder to create a new publisher file called “py_minimal_publisher.py”.

Type the following code inside py_minimal_publisher.py:

#! /usr/bin/env python3

"""

Description:

This ROS 2 node periodically publishes "Hello World" messages on a topic.

It demonstrates basic ROS concepts such as node creation, publishing, and

timer usage.

-------

Publishing Topics:

The channel containing the "Hello World" messages

/py_example_topic - std_msgs/String

-------

Subscription Topics:

None

-------

Author: Addison Sears-Collins

Date: November 4, 2024

"""

import rclpy # Import the ROS 2 client library for Python

from rclpy.node import Node # Import the Node class for creating ROS 2 nodes

from std_msgs.msg import String # Import the String message type for publishing

class MinimalPyPublisher(Node):

"""Create MinimalPyPublisher node.

"""

def __init__(self):

""" Create a custom node class for publishing messages

"""

# Initialize the node with a name

super().__init__('minimal_py_publisher')

# Creates a publisher on the topic "topic" with a queue size of 10 messages

self.publisher_1 = self.create_publisher(String, '/py_example_topic', 10)

# Create a timer with a period of 0.5 seconds to trigger the callback function

timer_period = 0.5 # seconds

self.timer = self.create_timer(timer_period, self.timer_callback)

# Initialize a counter variable for message content

self.i = 0

def timer_callback(self):

"""Callback function executed periodically by the timer.

"""

# Create a new String message object

msg = String()

# Set the message data with a counter

msg.data = 'Hello World: %d' % self.i

# Publish the message on the topic

self.publisher_1.publish(msg)

# Log a message indicating that the message has been published

self.get_logger().info('Publishing: "%s"' % msg.data)

# Increment the counter for the next message

self.i = self.i + 1

def main(args=None):

"""Main function to start the ROS 2 node.

Args:

args (List, optional): Command-line arguments. Defaults to None.

"""

# Initialize ROS 2 communication

rclpy.init(args=args)

# Create an instance of the MinimalPublisher node

minimal_py_publisher = MinimalPyPublisher()

# Keep the node running and processing events.

rclpy.spin(minimal_py_publisher)

# Destroy the node explicitly

# (optional - otherwise it will be done automatically

# when the garbage collector destroys the node object)

minimal_py_publisher.destroy_node()

# Shutdown ROS 2 communication

rclpy.shutdown()

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Execute the main function if the script is run directly

main()

I added detailed comments to the code so you can understand what each piece is doing.

To generate the comments for each class and function, you follow these steps for the autoDocstring package.

Your cursor must be on the line directly below the definition of the function or class to generate all the comments.

Then press enter after opening docstring with triple quotes (“””).

What we are going to do in this node is publish the string “Hello World” to a topic named /py_example_topic. The string message will also contain a counter that keeps track of how many times the message has been published.

We chose the name /py_example_topic for the topic, but you could have chosen any name.

Create the __init__.py file

Now, we need to configure our package so that ROS 2 can discover this Python node we just created. To do that, we need to create a special initialization file.

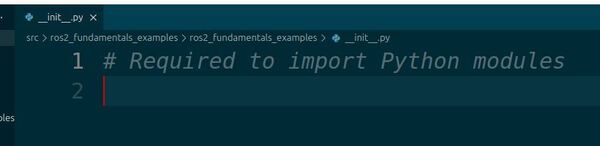

Right-click on the name of the ros2_ws/src/ros2_fundamentals_examples/ros2_fundamentals_examples folder, and create an empty script called

__init__.pyHere is what the file should look like:

The presence of _ _init_ _.py explicitly designates a directory as a Python package. This enables Python’s import machinery to recognize and treat it as a cohesive collection of Python code.

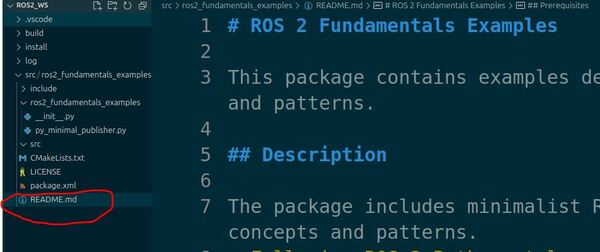

Create a README.md

Now let’s create a README.md file. A README.md file is a plain text file that serves as an introduction and explanation for a project, software, or package. It’s like a welcome mat for anyone encountering your work, providing essential information and guidance to get them started.

Right-click on the package (…/src/ros2_fundamentals_examples/), and create a new file named README.md.

You can find a syntax guide on how to write a README.md file here on GitHub.

To see what the README.md file looks like, you can right-click on README.md on the left pane and click “Open Preview”.

# ROS 2 Fundamentals Examples

This package contains examples demonstrating fundamental ROS 2 concepts and patterns.

## Description

The package includes minimalist ROS 2 code to demonstrate important ROS 2 concepts and patterns.

- Following ROS 2 Python style guidelines

## Prerequisites

- ROS 2 installed

- Python 3

- Created ROS 2 workspace (`ros2_ws`)

## Author

Addison Sears-Collins

Modify the package.xml File

Now let’s open the package.xml file. Make sure it looks like this.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<?xml-model href="http://download.ros.org/schema/package_format3.xsd" schematypens="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema"?>

<package format="3">

<name>ros2_fundamentals_examples</name>

<version>0.0.0</version>

<description>Basic examples demonstrating ROS 2 concepts</description>

<maintainer email="automaticaddison@example.com">Addison Sears-Collins</maintainer>

<license>Apache-2.0</license>

<!--Specify build tools that are needed to compile the package-->

<buildtool_depend>ament_cmake</buildtool_depend>

<buildtool_depend>ament_cmake_python</buildtool_depend>

<!--Declares package dependencies that are required for building the package-->

<depend>rclcpp</depend>

<depend>rclpy</depend>

<depend>std_msgs</depend>

<!--Specifies dependencies that are only needed for testing the package-->

<test_depend>ament_lint_auto</test_depend>

<test_depend>ament_lint_common</test_depend>

<export>

<build_type>ament_cmake</build_type>

</export>

</package>

The package.xml file is an important part of any ROS 2 package. Think of package.xml as your ROS 2 package’s identification card. Just like how your ID card contains essential information about you – your name, date of birth, ID number, and address – package.xml holds key details about your package.

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements you’ll find in a typical package.xml file. You don’t need to memorize this. Just come back to this tutorial if you are ever in doubt:

1. Basic Information:

- name: The unique identifier for the package, often corresponding to the folder name.

- version: The package’s version.

- description: A brief explanation of the package’s purpose and functionality.

- maintainer: Who is maintaining the package.

- license: Specifies the license under which the package is distributed, indicating how others are permitted to use, modify, and redistribute the package’s code and other assets.

2. Dependencies:

- buildtool_depend: Build tools (like compilers) needed for building the package.

- depend: Package dependencies that are required for building the package. Since we are publishing a message of type std_msgs/String, we need to make sure we declare a dependency on the std_msgs ROS 2 package.

- test_depend: Tools used for checking the code for bugs and errors.

3. Build Configuration:

- export: Defines properties and settings used during package installation.

- build_type: Specifies the build system (e.g., ament_cmake).

Modify the CMakeLists.txt File

Now let’s configure the CMakeLists.txt file. A CMakeLists.txt file in ROS 2 defines how a ROS 2 package should be built. It contains instructions for building and linking the package’s executables, libraries, and other files.

I have commented out sections which we are going to use in the future:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.8)

project(ros2_fundamentals_examples)

# Check if the compiler being used is GNU's C++ compiler (g++) or Clang.

# Add compiler flags for all targets that will be defined later in the

# CMakeLists file. These flags enable extra warnings to help catch

# potential issues in the code.

# Add options to the compilation process

if(CMAKE_COMPILER_IS_GNUCXX OR CMAKE_CXX_COMPILER_ID MATCHES "Clang")

add_compile_options(-Wall -Wextra -Wpedantic)

endif()

# Locate and configure packages required by the project.

find_package(ament_cmake REQUIRED)

find_package(ament_cmake_python REQUIRED)

find_package(rclcpp REQUIRED)

find_package(rclpy REQUIRED)

find_package(std_msgs REQUIRED)

# Define a CMake variable named dependencies that lists all

# ROS 2 packages and other dependencies the project requires.

set(dependencies

rclcpp

std_msgs

)

# Add the specified directories to the list of paths that the compiler

# uses to search for header files. This is important for C++

# projects where you have custom header files that are not located

# in the standard system include paths.

include_directories(

include

)

# Tells CMake to create an executable target named minimal_cpp_publisher

# from the source file src/minimal_cpp_publisher.cpp. Also make sure CMake

# knows about the program's dependencies.

#add_executable(minimal_cpp_publisher src/minimal_cpp_publisher.cpp)

#ament_target_dependencies(minimal_cpp_publisher ${dependencies})

#add_executable(minimal_cpp_subscriber src/minimal_cpp_subscriber.cpp)

#ament_target_dependencies(minimal_cpp_subscriber ${dependencies})

# Copy necessary files to designated locations in the project

install (

DIRECTORY ros2_fundamentals_examples

DESTINATION share/${PROJECT_NAME}

)

install(

DIRECTORY include/

DESTINATION include

)

# Install cpp executables

#install(

# TARGETS

# minimal_cpp_publisher

# minimal_cpp_subscriber

# DESTINATION lib/${PROJECT_NAME}

#)

# Install Python modules for import

ament_python_install_package(${PROJECT_NAME})

# Add this section to install Python scripts

install(

PROGRAMS

ros2_fundamentals_examples/py_minimal_publisher.py

DESTINATION lib/${PROJECT_NAME}

)

# Automates the process of setting up linting for the package, which

# is the process of running tools that analyze the code for potential

# errors, style issues, and other discrepancies that do not adhere to

# specified coding standards or best practices.

if(BUILD_TESTING)

find_package(ament_lint_auto REQUIRED)

# the following line skips the linter which checks for copyrights

# comment the line when a copyright and license is added to all source files

set(ament_cmake_copyright_FOUND TRUE)

# the following line skips cpplint (only works in a git repo)

# comment the line when this package is in a git repo and when

# a copyright and license is added to all source files

set(ament_cmake_cpplint_FOUND TRUE)

ament_lint_auto_find_test_dependencies()

endif()

# Used to export include directories of a package so that they can be easily

# included by other packages that depend on this package.

ament_export_include_directories(include)

# Generate and install all the necessary CMake and environment hooks that

# allow other packages to find and use this package.

ament_package()

The standard sections of a CMakeLists.txt file for ROS 2 are as follows:

1. cmake_minimum_required(VERSION X.X)

Specifies the minimum required version of CMake for building the package. This is typically set to a version that is known to be compatible with ROS 2.

2. project(ros2_fundamentals_examples)

Specifies the name of the ROS 2 package.

3. find_package(ament_cmake REQUIRED)

Finds and loads the necessary dependencies for the ROS 2 package.

4. set(dependencies…):

Lists all the packages and libraries needed by the project.

6. include_directories(include):

Tells the compiler where to find header files for C++ code. We aren’t going to use this line yet because our publisher is written in Python.

7. add_executable(…):

Creates an executable program using the specified source file. We will add this publisher in the next tutorial.

8. ament_target_dependencies(<program name>. ${dependencies}):

Links the program with the required dependencies.

9. install(DIRECTORY <project_name> scripts DESTINATION share/${PROJECT_NAME}):

Copies folders to the project’s install directory for sharing.

10. install(DIRECTORY include/ DESTINATION include):

Installs header files to the project’s install directory.

11. install(TARGETS <program names go here separated by space> DESTINATION lib/${PROJECT_NAME}):

Installs the built C++ programs to the project’s install directory. We will write these C++ programs later.

12. ament_python_install_package(${PROJECT_NAME}):

Installs Python modules for the project.

13. if(BUILD_TESTING) … endif():

Sets up code checking (linting) if testing is enabled.

14. ament_export_include_directories(include):

Allows other packages to use this package’s header files.

15. ament_package():

Generates necessary files for other packages to find and use this package.

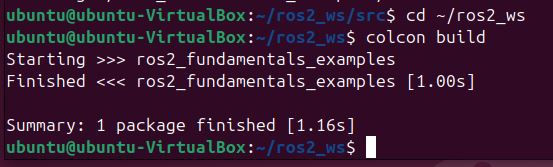

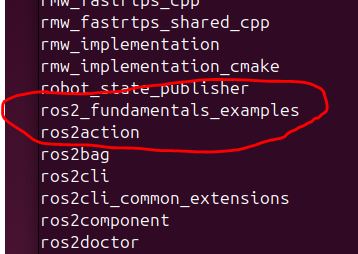

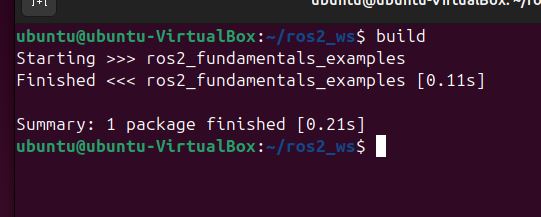

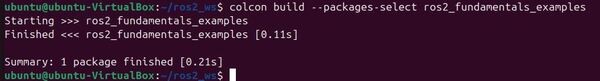

Build the Workspace

Now that we have created our script and configured our build files, we need to build everything into executables so that we can run our code.

Open a terminal window, and type:

buildIf this command doesn’t work, type these commands:

echo "alias build='cd ~/ros2_ws/ && colcon build && source ~/.bashrc'" >> ~/.bashrcbuildRun the Node

Let’s run our node. Here’s the general syntax:

ros2 run <package_name> <python_script_name>.pyHere’s a breakdown of the components:

- <package_name>: Replace this with the name of your ROS 2 package containing the Python script.

- <python_script_name>.py: Replace this with the name of your Python script file that contains the ROS 2 node.

Note that, you can use the tab button to autocomplete a partial command. For example, type the following and then press the TAB button on your keyboard.

ros2 run ros2_fundamentals_examples py [TAB]After autocompletion, the command looks like this:

ros2 run ros2_fundamentals_examples py_minimal_publisher.pyNow, press Enter.

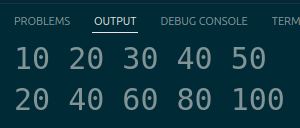

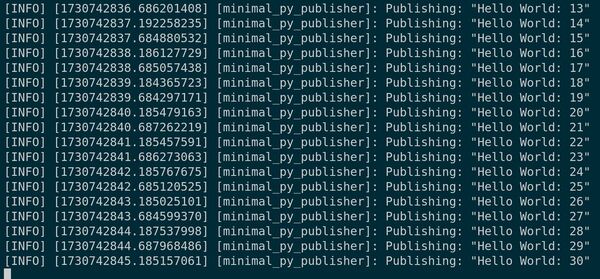

Here is what the output looks like:

Examine Common ROS 2 Commands

Topics

Open a new terminal window.

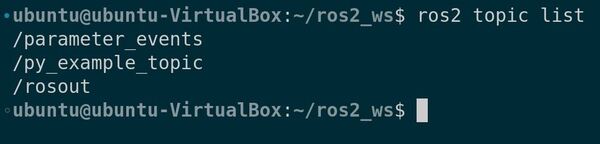

Let’s see a list of all currently active topics.

ros2 topic list

We see we have three active topics:

/parameter_events and /rosout topics appear even when no nodes are actively running due to the presence of system-level components and the underlying architecture of the ROS 2 middleware.

The /parameter_events topic facilitates communication about parameter changes, and the /rosout topic provides a centralized way to access log messages generated by different nodes within the ROS 2 network. You can ignore both topics.

/py_example_topic is the topic we created with our Python node. Let’s see what data is being published to this topic.

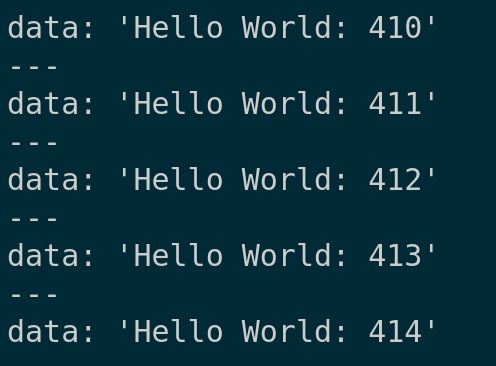

ros2 topic echo /py_example_topicYou can see the string message that is being published to this topic, including the counter integer we created in the Python script.

Press CTRL + C in the terminal to stop the output.

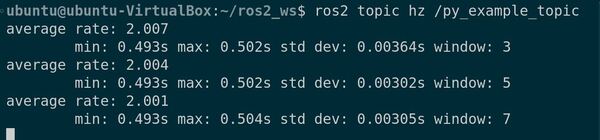

At what frequency is data being published to this topic?

ros2 topic hz /py_example_topicData is being published at 2Hz, or every 0.5 seconds.

Press CTRL + C in the terminal to stop the output.

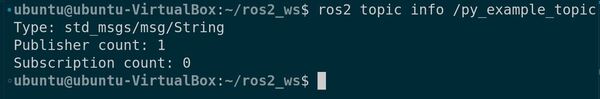

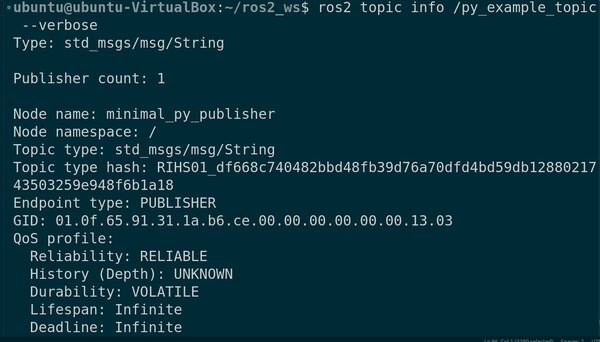

What type of data is being published to this topic, and how many nodes are publishing to this topic?

ros2 topic info /py_example_topic

To get more detailed information about the topic, you could have typed:

ros2 topic info /py_example_topic --verbose

You can see a list of the ROS 2 topic commands at this page here.

Nodes

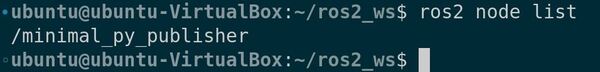

What are the currently active nodes?

ros2 node list

Let’s find out some more information about our node.

ros2 node info /minimal_py_publisher

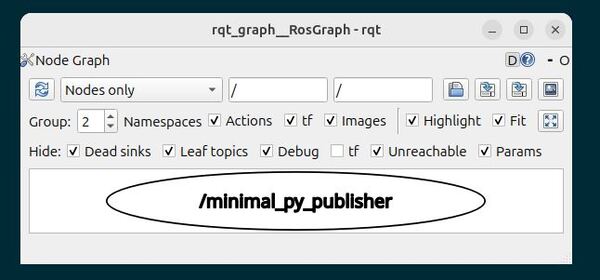

Check out how all the nodes are communicating using this command:

rqt_graphClose the Node

Now go back to the terminal where your py_minimal_publisher.py script is running and press CTRL + C to stop its execution.

To clear the terminal window, type:

clearCongratulations! You have written your first publisher in ROS 2.

In this example, you have written a publisher to publish a basic string message. And although it is not the most exciting node, it is similar to the kinds of nodes you will write again and again over the course of your robotics career.

On a real robot, you will write many different publishers that publish data that gets shared by the different components of a robot: strings, LIDAR scan readings, ultrasonic sensor readings, camera frames, 3D point cloud data, integers, float values, battery voltage readings, odometry data, and much more.

The code you wrote in this tutorial serves as a template for creating these more complex publishers. All publishers in ROS 2 are based on the same basic framework as the node you just wrote, py_minimal_publisher.py.

That’s it. Keep building!