In this tutorial, we will explore object-oriented programming basics in C++.

Prerequisites

Implementing Classes and Objects

In this tutorial, we’re going to enhance our understanding of object-oriented programming in C++ by creating a class to represent a robotic distance sensor. Sensors are pivotal in robotics, providing the ability to perceive and interact with the environment.

Open a terminal window, and type this:

cd ~/Documents/cpp_tutorial

code .

Let’s begin by creating a new C++ file and naming it distance_sensor.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// Definition of the DistanceSensor class

class DistanceSensor {

private:

double range; // Maximum range of the sensor in meters

public:

// Constructor that initializes the sensor's range

DistanceSensor(double max_range) : range(max_range) {}

// Method to display the maximum range of the sensor

void displayRange() {

cout << "Sensor maximum range: " << range << " meters" << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Creating an instance of DistanceSensor with a range of 1.5 meters

DistanceSensor front_sensor(1.5);

front_sensor.displayRange(); // Calling the display method

return 0;

}

Here’s a breakdown of what we just wrote:

#include <iostream> allows us to use input and output operations, specifically cout for displaying text.

We declare a class named DistanceSensor that models a distance sensor in a robotic system. It includes:

- A private data member range, which is not accessible outside the class. This encapsulation is a key principle of object-oriented programming, protecting the integrity of the data.

- A public constructor that initializes the range when a new object is created. The initializer list (: range(max_range)) directly sets the range member variable.

- A public method displayRange() that outputs the range to the console. This method demonstrates how objects can have behaviors through functions.

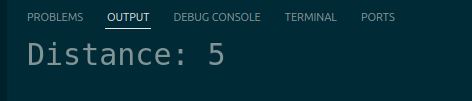

Run the code.

This example shows how to define a class with private data and public methods, encapsulating the functionality in a way that’s easy to manage and expand for larger robotic systems. Using classes like this helps keep your robot’s code organized and modular.

Using Header Files

Let’s learn how to use header files in C++ to organize our code. Whether you’re building a small project or a complex robotics system, understanding header files is important.

Header files (typically ending in .hpp or .h) serve as a “contract” or “interface” for your code. They declare what functionality is available without specifying how that functionality is implemented. This separation between declaration and implementation is a key principle in C++ programming.

Let’s create a minimal example with two files:

- robot.hpp – Our header file containing the class declaration

- robot.cpp – Our implementation file containing the actual code and main function

Type the following code into robot.hpp:

#ifndef ROBOT_HPP_

#define ROBOT_HPP_

class Robot {

public:

void greet();

};

#endif

Let’s break down what’s happening here:

- #ifndef, #define, and #endif are called “include guards”. They prevent multiple inclusions of the same header file, which could cause compilation errors.

- The class Robot is declared with a single public method greet().

- Notice we only declare what the class can do, not how it does it.

Now type the following code into robot.cpp:

#include "robot.hpp"

#include <iostream>

void Robot::greet() {

std::cout << "Hello, I am a robot." << std::endl;

}

int main() {

Robot my_robot;

my_robot.greet();

return 0;

}

Here’s what’s happening in our implementation file:

- #include “robot.hpp” tells the compiler to insert the contents of our header file here.

- #include <iostream> gives us access to input/output functionality.

- We implement the greet() method using Robot::greet() syntax to specify it belongs to the Robot class.

- The main() function creates a robot object and calls its method.

When you use #include, the compiler looks for the specified file in different locations depending on how you include it:

- #include “file.hpp” (with quotes): Searches first in the current directory, then in compiler-specified include paths

- #include <file.hpp> (with angles): Searches only in compiler-specified system include paths (e.g. /usr/include)

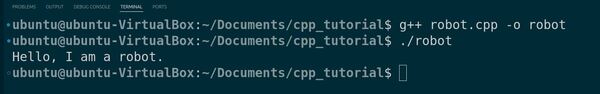

Run the robot.cpp code using Code Runner.

You could also run the code as follows…

Open a terminal in Visual Studio Code by navigating to ‘Terminal’ in the top menu and clicking on ‘New Terminal’. Type the following command to compile:

g++ robot.cpp -o robot

This command compiles robot.cpp, and because robot.hpp is in the same directory and included in robot.cpp, the compiler finds it without issue.

If robot.hpp were in another directory, you would need to tell the compiler where to find it using the -I option followed by the path to the directory.

Run the program with:

./robot

Defining Access Specifiers: Private, Protected, and Public

Let’s explore access specifiers in C++, which are important for object-oriented programming in robotics applications. Access specifiers determine the visibility and accessibility of class members, ensuring proper encapsulation and data protection.

Let’s create a new C++ file and name it access_specifiers.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

class Robot {

private:

int battery_level_; // Only accessible within the class

protected:

int max_speed_; // Accessible within the class and derived classes

public:

Robot(int battery, int speed) {

battery_level_ = battery;

max_speed_ = speed;

}

void print_status() {

std::cout << "Battery Level: " << battery_level_ << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max Speed: " << max_speed_ << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

Robot my_robot(75, 10);

my_robot.print_status(); // Allowed as print_status() is public

return 0;

}

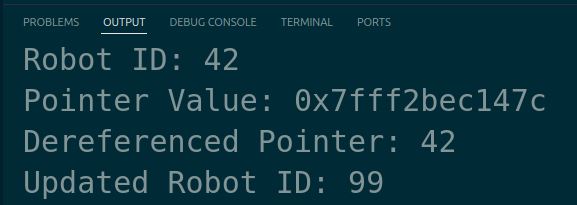

In this example, we define a Robot class with three members:

- battery_level_ (private): Only accessible within the Robot class itself.

- max_speed_ (protected): Accessible within the Robot class and any classes derived from it.

- print_status() (public): Accessible from anywhere, including outside the class.

The private specifier ensures that the battery_level_ variable cannot be accessed or modified directly from outside the class, promoting data encapsulation and preventing unintended modifications.

The protected specifier allows the max_speed_ variable to be accessed by the Robot class and any classes derived from it, facilitating code reuse and inheritance in robotics applications.

The public specifier makes the print_status() function accessible from anywhere, allowing other parts of the program to retrieve and display the robot’s status.

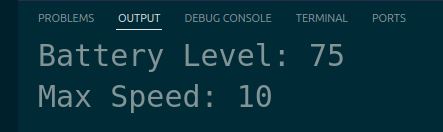

Run the code.

You should see the robot’s battery level and max speed printed in the terminal.

Employing the static Keyword

Let’s explore the static keyword in C++ and how it can be useful in robotics projects.

The static keyword in C++ has two primary uses:

- Static variables: When a variable is declared as static inside a function, it retains its value between function calls.

- Static member variables and functions: When a member variable or function is declared as static in a class, it belongs to the class itself rather than any specific instance of the class.

Create a new C++ file and name it static_example.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

void increment_counter() {

static int count = 0;

count++;

std::cout << "Counter: " << count << std::endl;

}

int main() {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

increment_counter();

}

return 0;

}

In this code, we define a function called increment_counter() that increments a static variable count each time it is called. The count variable is initialized to 0 only once, and its value persists between function calls.

In the main() function, we call increment_counter() five times using a for loop.

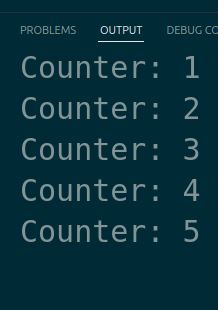

Run the code.

You should see the value of count increasing with each function call, demonstrating that the static variable retains its value between calls.

This example illustrates how static variables can be useful in robotics projects. For instance, you might use a static variable to keep track of the total distance traveled by a robot or to count the number of objects a robot has picked up.

Static member variables and functions are also valuable in robotics, as they allow you to define properties and behaviors that are shared by all instances of a class, such as a robot’s maximum speed or a function that calculates the inverse kinematics for a robotic arm.

Implementing Constructors

Let’s learn about constructors in C++ and how they can be used in robotics projects.

Constructors are special member functions in C++ that are automatically called when an object of a class is created. They are used to initialize the object’s data members and perform any necessary setup.

Create a new C++ file and name it constructor_example.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Robot {

public:

Robot(std::string name, int x, int y) {

name_ = name;

x_ = x;

y_ = y;

std::cout << "Robot " << name_ << " created at position (" << x_ << ", " << y_ << ")" << std::endl;

}

private:

std::string name_;

int x_;

int y_;

};

int main() {

Robot robot1("AutomaticAddisonBot1", 0, 0);

Robot robot2("AutomaticAddisonBot2", 10, 20);

return 0;

}

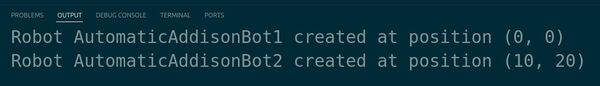

In this code, we define a Robot class with a constructor that takes three parameters: name, x, and y. The constructor initializes the name_, x_, and y_ data members of the class and prints a message indicating the robot’s name and initial position.

In the main() function, we create two Robot objects, robot1 and robot2, with different names and initial positions.

Run the code.

You should see messages in the terminal indicating the creation of the two robots with their respective names and initial positions.

This example demonstrates how constructors can be used to initialize objects in a robotics project. You can use constructors to set up a robot’s initial state, such as its position, orientation, or any other relevant parameters.

Overloading Functions

Let’s explore function overloading in C++ and how you can apply it in your robotics projects.

Function overloading is a feature in C++ that allows you to define multiple functions with the same name but different parameter lists. The compiler distinguishes between the overloaded functions based on the number, types, and order of the arguments passed when the function is called.

Create a new C++ file and name it overloading_example.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

void move_robot(int distance) {

std::cout << "Moving robot forward by " << distance << " units" << std::endl;

}

void move_robot(int x, int y) {

std::cout << "Moving robot to position (" << x << ", " << y << ")" << std::endl;

}

int main() {

move_robot(10);

move_robot(5, 7);

return 0;

}

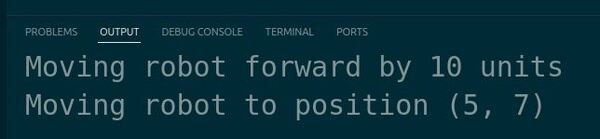

In this code, we define two functions named move_robot. The first function takes a single integer parameter distance, while the second function takes two integer parameters x and y.

The first move_robot function simulates moving the robot forward by a specified distance, while the second move_robot function simulates moving the robot to a specific position on a 2D plane.

In the main() function, we call both overloaded move_robot functions with different arguments.

Run the code.

You should see messages in the terminal indicating the robot’s movement based on the arguments passed to the overloaded move_robot functions.

Function overloading is particularly useful when you want to provide multiple ways to perform a similar action, such as moving a robot, but with different parameters or units of measurement.

Implementing Destructors

Let’s learn about destructors in C++ and how you can use them in robotics projects.

Destructors are special member functions in C++ that are automatically called when an object of a class is destroyed. They are used to clean up any resources allocated by the object during its lifetime, such as memory, file handles, or network connections.

Create a new C++ file, and name it destructor_example.cpp.

Type the following code into the editor:

#include <iostream>

class RobotController {

public:

RobotController() {

std::cout << "Robot controller initialized" << std::endl;

}

~RobotController() {

std::cout << "Robot controller shutting down" << std::endl;

// Clean up resources, e.g., close connections, release memory

}

void control_robot() {

std::cout << "Controlling robot..." << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

RobotController controller;

controller.control_robot();

return 0;

}

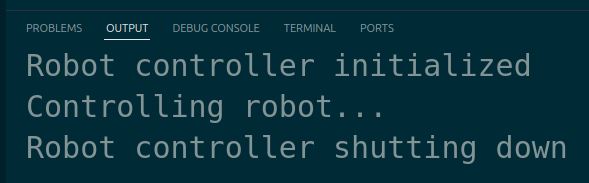

In this code, we define a RobotController class with a constructor and a destructor. The constructor is called when a RobotController object is created, and it prints a message indicating that the controller has been initialized.

The destructor is prefixed with a tilde (~) and has the same name as the class. It is called when the RobotController object goes out of scope or is explicitly deleted.

In this example, the destructor prints a message indicating that the controller is shutting down. In a real-world scenario, the destructor would also clean up any resources allocated by the controller.

The control_robot() function simulates the controller performing some robot control tasks.

In the main() function, we create a RobotController object named controller and call its control_robot() function.

Run the code.

You should see messages in the terminal indicating the initialization of the robot controller, the control of the robot, and finally, the shutting down of the controller when the object is destroyed.

This example demonstrates how destructors can be used in robotics projects to ensure proper cleanup and resource management. Destructors are particularly important when working with limited resources or when managing external connections, such as communication with hardware or other systems.

Thanks, and I’ll see you in the next tutorial.

Keep building!